George Grosz: Behold the Man

When I was a teenager in the late 1960’s, I found an art book in my local library titled, Ecco Homo (Behold the Man). As my first real introduction to German Expressionist art, it was an encounter that profoundly altered my life as an artist.

Ecco Homo was a portfolio of prints created by artist, George Grosz, in 1923. That same year, German authorities confiscated the artist’s prints and fined him for “offending public morals”. The state had already gone after Grosz in 1920 for his print portfolio, Gott mit Uns (God is with Us), which mocked and denigrated German soldiers and their officers.

The unrepentant artist released another print portfolio in 1928 titled, Hintergrund (Background). In addition to insulting the militarists, the prints took aim at ultra-nationalist clerics, directly linking the German church with militarism. Grosz was arrested and put on trial for blasphemy and the court decided that one of the offending prints, Christ With a Gas Mask, would be destroyed. Of course, history vindicated George Grosz, who correctly identified and portrayed the forces that would plunge Germany into the nightmare years of fascism.

As a budding artist I was profoundly influenced by Grosz, and I remain in awe of him to this day. Being in Los Angeles, it’s unlikely I’ll be attending the exhibit of his works at the Heckscher Museum of Art in New York City, but perhaps my writing about the show will inspire people on the east coast to attend. George Grosz: Selections from the Permanent Collection, now on view at the museum until August 14th, 2005, includes Grosz’s, Sonnenfinsternis (Eclipse of the Sun).

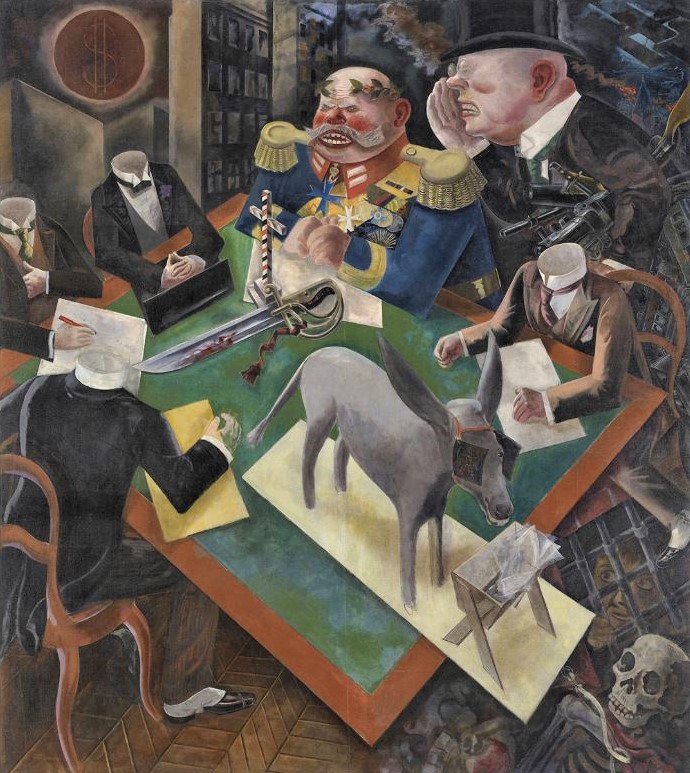

Painted in 1926, the work is a denunciation of the forces of war. Headless bureaucrats sit at a table where a bloated Caesar-like general presides, his bloody sword placed on the table next to a crucifix painted in the German national colors. A rich industrialist with weapons of war tucked under his arm, leans forward to whisper into the commandant’s ear. Under the table we can see a prison cell, where a prisoner peers out at the spectacle.

The sun is depicted in silhouette, hanging in the upper left corner of the painting and literally eclipsed by a dollar sign. Here’s what Grosz said about his painting, “Since the politicians seem to have lost their heads, the army and capitalists are dictating what is to be done. The people, symbolized by the blinkered ass… simply eat what is put before them.” I saw this very painting some years ago at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art (LACMA). I was admiring the work with a group of strangers, when one of them said out loud to no one in particular, “My god, this could have been painted about today’s world!”

What I learned from Grosz could best be summed up in his own words, “For me art is not a matter of aesthetics, no musical scribbling to be responded to or fathomed only be a sensitive educated few. Drawing once more must subordinate itself to a social purpose.”

Grosz taught me that great art had to encompass more than just technical prowess, it also had to embrace moral responsibility and awareness. In 1913 he wrote to a friend:

“There can be no doubt that my drawings were some of the strongest public statements against a certain German brutality. Today they are truer than ever – one day, in a more ‘humane’ period, one will exhibit them as one does now with Goya’s pictures.”

While we don’t yet live in the ‘humane’ period Grosz worked towards, we can still at least appreciate the artist’s extraordinary vision.