Bouguereau & His American Students

What possible relevance could Adolphe-William Bouguereau, a French academic painter from the Victorian age, have in today’s world? That in essence is what the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette asked when it interviewed me regarding a display of the painter’s works at the Frick Art & Historical Center of Pennsylvania. The Frick exhibit, In the Studios of Paris: William Bouguereau & His American Students, runs from July 6th, 2007, to October 14th, 2007, and it’s the first show of its kind to examine Bouguereau’s past position as a leading teacher of painting.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette thought my input as a contemporary realist painter and critic of Bouguereau and his present-day followers, would make for a well rounded examination of Bouguereau in current times. In addition to me, the newspaper interviewed Dr. Eric M. Zafran, an authority on French academic painting and the Curator of European Art at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut. Also interviewed was art historian Charles Pearo and artist-writer, Claudia Giannini. Not to be left out of any discussion pertaining to Bouguereau, opinions regarding the legacy of the academic painter were expressed by his chief devotee, Mr. Fred Ross, Chairman of the Art Renewal Center. You can read the full Pittsburgh Post-Gazette interview here.

Today as painting evolves and struggles to find its place in the early 21st century, Bouguereau (1825-1905; pronounced: boo-ger-Oh), becomes relevant since he represents one of two elemental paths contemporary painters can choose from – painting as a conservative expression of tradition, or an innovative expression of change. Obviously Bouguereau embodies the former, and aside from the fact that I believe we have many things to learn from academic artists when it comes to the technical handling of paint, I stand with those who seek new approaches to the problems of modern-day painting.

In a notice on the official Frick website announcing a talk by Dr. Zafran on the subject of the academic painter, it’s stated that: “To appreciate Bouguereau one has to essentially forget the twentieth century and modern art and enter into the spirit of the nineteenth century.” I might add that one would also have to forget what was happening in the 19th century as well, as Bouguereau’s art represented a headlong flight from the pressing realities of his time. We shouldn’t feel smug about this either, as many of today’s artists share that same zeal for their ivory towers.

As a youth Bouguereau studied at the conservative official academy, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and eventually he would be elected to head the Académie des Beaux-Arts. But Bouguereau lived during a period of earthshaking change, witnessing the rise of industrialism and the working class, women demanding the vote and inclusion into positions of power, the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune of 1871 and the wave of reprisal killings that took the lives of tens of thousands of Parisian Communards. Yet, in Bouguereau’s paintings there is not the slightest inkling of any of this. And therein lies the problem with an uncritical appreciation of William Bouguereau. It’s as if his meticulously painted Satyrs, winged celestial angels and plump innocent cherubs were intentionally meant to conceal the grinding poverty and growing class conflict of his day – and indeed, that’s exactly the role his escapist canvases filled.

Defenders of Bouguereau will point to his “sympathetic” portraits of the poor, which for the most part are sweet nonthreatening portraits of healthy young peasant girls that reveal nothing about the lives of the dispossessed. Such paintings were popular with Victorians, who preferred grimy reality be covered by a veneer of sentimentality. One need only compare Vincent van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885) to Bouguereau’s The Haymaker (1869), to understand my point. Van Gogh gave us a harshly realistic and unromanticized portrayal of people who worked their fingers to the bone just to maintain a subsistence level existence. His peasants are the color of the earth they dig. Their backbreaking labor under a merciless sun has turned them old before their time. They eat their modest dinner of boiled potatoes with calloused and knobby hands. Van Gogh has shown us real life. By contrast, one can’t imagine Bouguereau’s fair-skinned and rosy-cheeked peasant girl engaged in the exhausting work of pitching hay from sunrise to sunset – let alone breaking out in a sweat over any type of manual labor. Bouguereau’s pleasant creature may make the more luminously beautiful painting – but she has nothing to do with real life.

Bouguereau once said, “One has to seek Beauty and Truth. There’s only one kind of painting. It’s the painting that presents the eye with perfection.” One can just imagine the rejoinder from those young upstart Impressionist painters of the late 1800’s, “Yes, but whose beauty? Whose truth?” Clearly, there was more than one kind of painting going on in Bouguereau’s day.

When it came to aesthetics, Bouguereau was a stalwart conservative who opposed the onrush of modern painting that was surging all around him. As a commanding figure in the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, Monsieur Bouguereau was able to successfully block, for a time, the rising tide of the Impressionists, who wanted to paint real life with all of its roughness. Instead of theatrical, highly finished paintings devoid of brushstrokes and based upon long past historical themes, the Impressionists concentrated on the world around them, insisting on colors and techniques as vibrant and bold as their chosen subject matter. Paul Cézanne blithely commented on Bouguereau’s success at hindering the Impressionists by referring to “the Salon de Monsieur de Bouguereau.” And it was Edgar Degas and his circle of associates who mocked the polished artifice of academic painting by referring to it as Bouguereaute (“bouguerated.”) In a letter written by Vincent Van Gogh, his opinion of Bouguereau couldn’t have been any clearer;

“I already told Gauguin in my last letter that if we painted like Bouguereau we could hope to make money, but the public will never change and likes only what is sweet and slick.”

However the most amusing story I know of concerning the clash between Bouguereau and the Impressionists came from Gauguin himself. In his autobiography, The Writings of a Savage, Gauguin tells of visiting the office of Henri Roujon, director of the Beaux-Arts. Hoping the academy would purchase some of the paintings he made in Tahiti, Gauguin wrote:

“So here I am in the office of the august Roujon, director of the Beaux-Arts. He said to me: ‘It is out of the question for me to encourage your art, which I find revolting and do not understand; your art is too revolutionary not to cause a scandal in our Beaux-Arts, of which I am the director, seconded by the inspectors.’ The curtain twitched and I thought I saw Bouguereau, another director (perhaps he’s the real one, who knows?). Undoubtedly he was not there, but I have a wayward imagination, and as far as I was concerned he was there. What! I a revolutionary, I who adore and respect Raphael? What is a revolutionary art? When does it cease being revolutionary? If the fact of not obeying Bouguereau or Roujon constitutes a revolution, then I confess I am the Auguste Blanqui of painting!” [Gauguin refers here to one of France’s most incorrigible revolutionists.]

Bouguereau openly proclaimed his aversion towards modern painting when he said, “In painting, I am an idealist. I see only the beautiful in art and, for me, art is the beautiful. Why reproduce what is ugly in nature? I do not see why it should be necessary. Painting what one sees just as it is – no – or at least, not unless one is immensely gifted. Talent is all redeeming and can excuse anything. Nowadays, painters go much too far, just as writers and realist novelists do. There is no way of telling where they’ll draw the line.”

Having defined painting and beauty in such a narrow manner, it’s hard to imagine that Bouguereau’s definition of good painting would have included Goya’s 1808 masterwork, The Third of May, which depicted a massacre of Spanish civilians at the hands of Napoleon’s invading army. Aside from rubbing our faces in an ugly and most unpleasant scene, Goya’s canvas must have appeared a raw, unfinished and crude monstrosity to the genteel eyes of academic painters like Bouguereau. Yet, does Goya’s tour de force not possess a terrible beauty? This is the reason for art critic Robert Hughes calling Francisco de Goya the first modern artist and an exemplar of modernism. All the same, Bouguereau reserved a special ire for those defiant painters of his own day, “One shouldn’t believe in all those so-called innovations. There is only one nature and only one way to see it. Nowadays, they want to succeed too fast, this is how they go about inventing new aesthetics, pointillism, pipisme! All this is just to make noise.”

Considered one of the top painters of his day, Bouguereau attracted thousands of aspiring artists, who joined his seminars and workshops at the Académie Julian and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Those students fervently sought instruction and criticism from the master, and in the last quarter of the 19th century, he offered training and advice to some 200 American student artists. The Frick exhibition combines 80 paintings, drawings and prints by Bouguereau as well as artworks by some of his more promising American students like Robert Henri, Elizabeth Gardner, Minerva Chapman, Cecilia Beaux, Eanger Irving Couse, Arthur Wesley Dow, Henri Tanner, and Lawton Parker.

Interestingly enough, while the American painter Robert Henri (pronounced ‘hen rye’) was one of Bouguereau’s star pupils at the Académie Julian, he would come to entirely repudiate academic painting and embrace Impressionism, only to reject it later on as a “new academicism.” Henri became one of the founders of the Ashcan School, the early 20th century movement of American realist painters whose works focused on the social realities of big city life. Ironically, Henri represented the modernist trend Bouguereau hoped to thwart, and essential lessons learned from the academic master were used by Henri as a springboard for the Ashcan revolution in art.

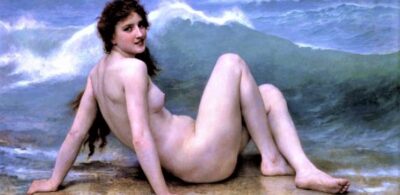

As an academic painter, Bouguereau’s hand provided endless melodramatic oil paintings dealing with Greek myths, Christian religious stories and genre scenes. That Bouguereau produced dazzling realist canvases demonstrating clear mastery over technique should be apparent, that these were saccharine works pleasing to the elites of his day and supportive of the status quo, should also go without saying. But I have a twofold question for contemporary artists that rises out of a study of Bouguereau and all that swirled around him, a query that accordingly makes a reconsideration of Bouguereau vital; do you have mastery over your chosen discipline, and if so, are you using it simply to please and support today’s equivalent of the academy?