TRASHMAN LIVES!

When Spain Rodriguez died on November 28, 2012, it was my friend and associate Lincoln Cushing who informed me by e-mail of the untimely passing.

I am certain a torrent of similar e-mails were exchanged around the nation as people shared their collective grief over the passing of a talented artist and illustrator who helped to shape the 1960s counterculture.

In the late 60s the cartoons of Spain loomed large in the eye-popping and vividly colorful pages of “underground” psychedelic publications. Zap Comix, that groundbreaking comic book magazine of the freak counterculture, published Spain’s cartoons in 1968, along with satirical works by Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Rick Griffin and other notables from the youth culture.

Members of my generation were liberated, or seriously warped – depending on who you talk to – by the material that appeared in Zap Comix. But is was Spain’s “Trashman” comic character, the one and only American superhero I would ever be a fan of, that left the deepest impression on me.

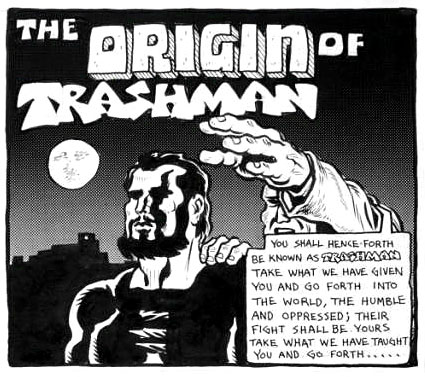

Developed in 1968, the Trashman comic story takes place in a totalitarian American future, telling the tale of a working class fellow named Harry Barnes. When Barnes discovers state forces have murdered his wife, he goes underground to escape their clutches.

Barnes is soon recruited by a shadowy anarcho-Marxist underground organization called the Sixth International, which trains Barnes in the use of weaponry, but also instructs him to make use of the “para-sciences”. Once Barnes masters clairvoyance, shape shifting, and other super powers, he is reborn as Trashman to wreak havoc upon fascist police and military forces and their wealthy ruling class paymasters.

Spain Rodriguez was a superlative draftsman, his pen and ink drawings done in black and white, whether sparsely or lavishly detailed, were always evocative.

I have an eternal appreciation for artworks created in black and white, a style of work not easily mastered, but Spain made it look easy; his unmistakable drawings were always a perfect balance of black and white.

Spain’s meticulous renderings of urban landscapes could be breathtaking in detail; his portraits of various characters revealed all of the decency or darkness of the human heart with just a few strokes of the pen. Unlike the works of other underground artists in his circle who were creating zany cartoons, Spain’s art possessed a certain seriousness – even when dealing with the improbable.

Spain’s Trashman antihero story became ubiquitous in certain counterculture circles in the late 1960s. The tale was no doubt an extension of Spain’s own world view and politics, but truth be told it was also a shared fantasy. Spain’s comic was born in a period of mass protest, government repression, and imperial war. Mind you, the assassinations of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Senator Robert Kennedy were recent murders, and the May 4, 1970 National Guard fatal shootings of antiwar student protestors at Kent State University was on the horizon. It was easy for young readers to believe that the Trashman comic was a look into our collective future.

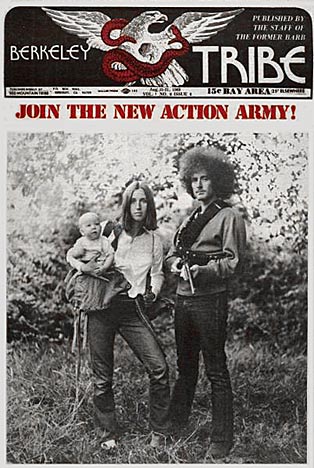

Many underground papers of the day carried the art of Rodriquez, indeed, in 1972 I acquired The Collected Trashman as published by the Red Mountain Tribe, the same radical collective that was printing and distributing the Berkeley Tribe underground paper in Berkeley, California. It is funny to think that as a teenager I could find the Berkeley Tribe and other radical newspapers at a local news stand in my quiet southern California neighborhood. Today that news stand is long gone, so are the area bookstores, all replaced by yuppie cafés and boutiques in a wave of late 90s gentrification. The one bookstore in my locale, a corporate chain, carries Batman, Spiderman, Avengers, X-Men, Superman, and all the rest… but no Trashman. Big surprise, eh?

Lincoln Cushing conducted an interview with Spain Rodriguez on September 28, 2010. Wanting to document Spain’s “important contribution to movement art”, Cushing included the interview in his book, All Of Us Or None: Social Justice Posters of the San Francisco Bay Area. The book’s 300 or so 60’s posters came from the massive All Of Us Or None (AOUON) poster archive collected and maintained by the brilliant Michael Rossman (1939-2008). There are six of Spain’s posters in the archive, and I am honored to say, six of my own print creations reside there as well. In the wake of Rossman’s untimely death, Cushing administered the AOUON collection until helping to arrange its donation to the Oakland Museum of California. Cushing granted me permission to publish his AOUON interview with Spain, an edited version of which follows:

Lincoln Cushing: “Who among underground comics artists did you find a connection around politics?”

Spain Rodriguez: “I always drew, and I went to art school. Underground cartoonists tend to be either left or apolitical. Gilbert Shelton is one who had political insight, a worthy hero and a better artist than he realizes. Now he’s over in Paris. I kind of got this generally good reception. The underground comics movement has a certain sort of camaraderie that is not specifically political. Crumb also has a progressive political outlook, somewhat more so in those days than today. His recent Genesis has an enlightening aspect to it. What Crumb did with Zap was turn it into a collective. He might have had some regrets about that later on, but we – the artists – own Zap. And that’s a big step. It’s a collective form by the most uncollective guys you can imagine.

A lot of us came from New York, and we all knew each other from the East Village Other – Bill Griffith, Art Spiegelman – and Trina Robbins, too, though she regards us as ‘those obnoxious male cartoonists,’ which is good, that’s what we are.

I’ve been political from very early on. In Buffalo [N.Y.] as a kid I knew something was extremely fucked up. I remember seeing this picture of a Mexican mural, with all these bigwigs sitting at a table, and one guy had one of those scientific funnels on his head, they were all pontificating and eating their little cakes, and all around them were these Mexicans with crossed bandoliers fingering their weapons in the doorways, and it instantly hit me. Suddenly I understood things. I drifted into the Socialist Labor Party. That was my early education. I had a philosophical inclination. When I read Marx that seemed to describe the world best.

Early on a guy named Ed Wolkenstein put out this little leaflet called ‘The Spirit and the Sword.‘ I did artwork for him, licked envelopes, did all that stuff to get it out. He took us out to the University of Buffalo, where I just assumed that people would tell us to never darken their doorway again, but we got this good reception. And of course this was the beginning of the antiwar movement. Me and Ed put up the first antiwar posters in Buffalo, 1965-1966. Maybe even 1964 – we did one on Goldwater’s election. I first came to the Bay Area in January of 1969, went back to Buffalo in March, then I came back in December.”

Lincoln Cushing: “Tell me about your view of 1950s culture”.

Spain Rodriguez: “It was certainly boredom, and the pressure to conform. I have my high school yearbook, and I’m the only one with sideburns. I went through a bunch of shit over that. I’ve always had a tendency to find the excitement, to find the cool thing. But that’s when rhythm and blues, and rock and roll started, so that certainly wasn’t boring. And in the neighborhood I lived in, there was a lot of stuff happening. There was pressure to conform, but there were also people that wouldn’t conform. With me it was always a struggle, being the nail that stuck out, getting pounded down.

There was also EC comics, which were real significant, and really hated and stabbed in the back by the whole comics code, which was one of the most repressive documents in history.

The Spaniards had this big empire, and then the Inquisition comes up. From a certain vantage point, the fact that they had the inquisition is a positive thing because they had something to ‘inquisit.’ The cultures they conquered didn’t have an inquisition, people readily accepted that if they didn’t go up and get their hearts cut out the sun would stop. No one said ‘Hey, let’s give it a try, don’t cut out my heart.’ In Spain you had this incredibly repressive thing, and you have to look at what prompted that.

EC comics had a social content. In fact my early thinking was shaped by that. The shock-suspense stories always had a social point, either the Ku Klux Klan or political corruption. They had a definitely liberal political angle. All these guys who came out of the Army and had G.I. Bill free college, a lot of them became artists, so there was this pool of great artists. Wallace Wood, Jack Davis, Severin, Elder. And the stuff sprang out for a few years, until ‘the hand’ crushed that.

Did you ever hear of the Resurgence Youth Movement? It was in the Lower East Side of NY, started by Jonathan Leek, who was in YPSL. When Kennedy was assassinated [11/22/1963] he issued a 12-page manifesto calling for all revolutionaries to go forth with pistol and dagger and put to death all public officials. Well, they booted his ass out. Then he got connected with the Wobblies, and they would put out this great stuff – ‘I dream of the days when motorcycles will roar down Park Avenue and the junkies will shoot up in your bathroom and the queens will prance on your lawn!’ – and all of that sort of came true.

You’d see him at antiwar demonstrations and there would be all the leftists on one side, and the Nazis on the other, and these guys would come in and attack the cops, and of course the cops would kick their ass. But I got to know those guys, and after smoking about nine joints they said ‘Yeah, we’ll kidnap Mayor Wagner’s son and we’ll try him according to people’s justice!’ and another guy would jump up and say ‘Yeah, then we’ll chop off his head with a guillotine!’ One guy was nuttier than the next.

All these historical things, they’re like some weird dice throw, and at some point it just comes to a boil. We’re living in interesting times. I’m not an anarchist, but I’m a libertarian – no one gets to run my personal life. I don’t believe the personal is political. I believe that the personal is nobody’s business. I’m not gay, but I support people’s right to live their own life as they see fit.”

While Trashman was unquestionably Spain’s most famous creation, it was certainly not his only one. Intensely interested in history, Spain created comic books about diverse historic figures from Marine Corps general Smedley Butler to Ernesto “Che” Guevara. He was a contributing artist to Wobblies!: A Graphic History of the Industrial Workers of the World, and the author of several original graphic novels. Really, his accomplishments are more than I can list.

The Burchfield Penny Art Center at Buffalo State College in Buffalo, New York is currently presenting the exhibit, Spain: Rock, Roll, Rumbles, Rebels, & Revolution. Beginning Sept. 14, 2012 and running until January 20, 2013, the exhibit features original drawings and reproductions from Spain’s complete body of work. Spain’s wife, Emmy-nominated filmmaker Susan Stern, produced a short film on Spain’s life and work for the Burchfield Penny Art Center exhibit; the insightful video can be viewed on YouTube. At the closing moment of Stern’s film, Spain made the following avowal, one that summed up his optimism: “I’ve seen many cool scenes, I have hope that cool scenes will keep on coming – I have faith in the revolution.”

Many an obituary will be written about Spain, most will focus on his being a mover and shaker in the world of comics, conveniently leaving aside his left-wing libertarian politics and thoughtful humanism. Paul Buhle, author and Senior Lecturer at Brown University, has possibly written the best published death notice on Spain for Dissent quarterly. Another insightful obit, Death of an American original, can be found on Salon.

What makes the Salon obituary so interesting is its ending, which presents two previously unpublished cartoon panels from Spain finished just prior to his death. The cartoons deal with the real-life story of cotton plantation slave James Roberts and his fellow slaves being enlisted by U.S. General Andrew Jackson to fight the British in the War of 1812. Though only eight panels long, the cartoon cuts like a knife. I must admit that I did not know the history revealed in Spain’s illustrated romp into the annals of America’s past, but that is the extraordinary thing about Spain Rodriguez; he continues to teach things to myself and others, even after moving on. Perhaps that is the best obituary I can offer.