Kent Twitchell: The End of Muralism?

On May 1st, 2008, the Los Angeles Times reported that famed L.A. muralist Kent Twitchell settled his lawsuit against the U.S. government for obliterating his six-story mural depiction of artist Ed Ruscha. Starting in 1978, it took Twitchell nine years to complete his mural on an outside wall of the L.A. headquarters of the U.S. Department of Labor. In 2006 the mural was deliberately painted over by a maintenance crew working for the government.

Federal and state laws protect commissioned murals in the City of Los Angeles from desecration or destruction; specifically, the federal Visual Artists Rights Act states that an artist must be given a ninety day notice before a building owner can paint over a mural. Twitchell received no such notice before his mural was arbitrarily destroyed, so he’s been awarded a $1.1 million settlement. To date it is the largest settlement to have been paid out to an artist under state or federal laws meant to protect artist’s rights – and I won’t hesitate to say that Twitchell fully deserves the money. I first heard of his mural being destroyed the day it happened, and without delay I called the L.A. arts community to his defense, so it’s gratifying to learn of Twitchell’s court victory – which also bodes well for all other muralists and artists creating public art across the country.

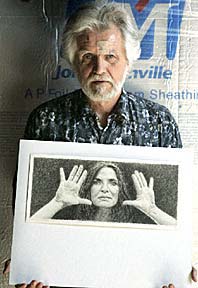

I met Twitchell a short while after the destruction of his mural, when photographer Gil Ortiz and I visited his Playa Vista, California studio in August of 2006 – hence much of what follows is based upon the chat I had with Twitchell during that visit. He was affable and friendly, revealing his feelings concerning the destruction of his Ed Ruscha mural, his life as an artist, and his views regarding the state of art in America today. No doubt Twitchell was irate over the destruction of his mural, but he possessed a clear-headed understanding of the social implications of his next move – a lawsuit against the U.S. government. At the time Twitchell told me; “I don’t want to blow this thing, I could hurt other artists if I blow this thing. I’ve got to make them know that they can’t just paint out a work of art just because they feel like it – there’s a law that they have to follow… they can paint it out, they can do whatever they want to it, they just have to be polite about it, but they were not.”

Known for his monumental works, I asked Twitchell if he ever created small scale artworks. “It’s a lot easier for me to work at least life-size. A lot of times when I work small I don’t pull it off, maybe two out of three times it’s ok. If I work life-size or bigger then almost everything I do I like.” Then he went bounding off to the second story of his studio to rustle through his archives. He returned with a portfolio of original sketches and lithographs that were delicately wrapped in acid free paper for purposes of preservation. Some of the drawings were of individuals that appear in his massive 405 Freeway mural, L.A. Marathon, a work that celebrates the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics but is unfortunately now damaged by graffiti. The drawings were composed of tightly woven crosshatched lines, the work of a highly skilled and disciplined draftsman. Twitchell chuckled and said “Sometimes I draw this way, not because it’s better, but because I’m obsessive compulsive – that’s who I am.”

Amongst the portfolio’s drawings and prints there was an amazing portrait of artist Lita Albuquerque. The lithograph was immediately recognizable as a print version of the huge Lita Albuquerque mural Twitchell painted alongside L.A.’s Harbor Freeway in 1983. I mentioned to him that I had just recently driven past the mural, and that it was almost completely destroyed by graffiti, to which Twitchell replied “I won’t have to repaint it because she’s so protected, all of that graffiti will come right off without damaging the original painting.” He then began explaining the process used to protect his street murals; “First there’s a type of wax that’s applied to the surface, followed by a coating of anti-graffiti material”, but Twitchell is well aware that restoration of a damaged mural is a relatively simple matter – and that a far bigger problem lies ahead for L.A. murals. Once restored to pristine condition they will immediately be defaced by graffiti taggers who respect nothing but their own trivial notoriety. Twitchell’s Albuquerque mural is still in situ, but as of this writing it’s completely buried under layers of graffiti – only Albuquerque’s eyes peer out from behind the shroud of spray paint vandalism.

Looking at Twitchell’s vast body of work, it’s easy to see that he has a passion for realism in painting, yet I wouldn’t call him a photo-realist. In spite of the fact that he uses modern techniques and equipment in his mural making, Twitchell is very much a traditionalist whose influences range from the Old Masters to Salvador Dali – he confided in me; “I want to paint one of my heroes, Grant Wood, the great American regionalist painter, who just tweaked the New York art establishment. He used to wear bib overalls – a brilliant man, went to Paris, learned about Modernism – he could do it as well as anybody, but he went back to Iowa and continued as a regionalist painter with Hicks, Benton, and the others – and he did it on purpose. So unpretentious, and that’s what art needs – unpretentiousness.”

A close up examination of Twitchell’s paintings reveals, not brush strokes, but tiny fields of pure color. He equates this to the Pointillism of French artist George Seurat, but notes that Seurat accomplished his paintings by using “pure colors, while I use values.” For all intents and purposes the outlines of Twitchell’s murals look like an extremely complicated paint by numbers drawing, but by stepping back just a few feet, the crazy quilt patchwork of values becomes a sharp focused realistic portrait.

Los Angeles has a deeply rooted tradition of public murals, from 1930s works by the likes of David Alfaro Siqueiros, Hugo Ballin, Dean Cornwell, and those artists working for the Works Progress Administration – to the late 1960s mural renaissance that sprang from the Chicano and African American social movements. However, the forward thinking community based activism that served as a catalyst for the city’s mural movement utterly collapsed decades ago – only to be replaced by a nihilistic apolitical narcissism that is daily expressed in graffiti vandalism.

At present some of L.A.’s murals have been destroyed outright, most others have fallen into a state of disrepair, and all are threatened by graffiti, especially outdoor murals located at street level. Scores of graffiti scarred murals are now simply beyond restoration. The L.A. Daily News addressed the issue in a 2007 article titled L.A.’s street murals disappearing, framing the problem in the following manner; “Once the mural capital of the world, Los Angeles has quietly surrendered that distinction to Philadelphia over the past five years. While the City of Brotherly Love spends $4.5 million to paint, restore and maintain its 2,700 murals, the City of Angels has just $20,000 to look after its documented murals, which once numbered 3,000. Artists say 60 percent of them – about 1,800 – now are either gone for good or have been nearly obliterated by tagging and vandalism.”

In 2006 I asked Twitchell what he thought about the state of the L.A. muralist movement and his answer was blunt, “The muralist movement is dead.” That’s a bitter pill to swallow, but any impartial observer would have to agree. The L.A. Times article that reported on Twitchell’s mural settlement quoted him as saying; “What’s really discouraging about most public art is the way that, in this city of ours, spray paint vandalism has kind of taken over the streets. What was once the mural capital is now the graffiti capital – although I don’t call it graffiti, I call it spray paint vandalism. We cannot coexist.”

I’m sure there are those who assume Twitchell is now “set for life” because of his settlement with the government, and that he can now retire to the lap of luxury. He is under no obligation to continue being a productive artist, and with his murals coming under attack from every direction, some would ask why doesn’t he just give up. That would be a complete misreading of the artistic spirit. Twitchell has devoted his life’s work to muralism, and knowing his devotion to the art, it’s a certainty he’d much rather have his mural of Ed Ruscha standing in pristine condition than to be awarded a cash settlement – no matter how large. Twitchell’s admonition that muralists “cannot coexist” with graffiti vandals is more an avowal to stand firm than it is a statement of surrender, and in the effort to re-establish the tradition of community based murals – I’ll stand shoulder to shoulder with the muralists.