Art Is For Everyone!

On September 27, 2013 the “liberal” American magazine, The New Republic, published an article by its editor-at-large Michael Kinsley. In the piece titled If They Replaced Detroit’s Art Treasures with Fakes, Would Anyone be Able to Tell?, Kinsley suggested that a proposal made by Harvard political scientist Edward Banfield 30 years ago might be the solution to the crisis at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). Banfield had written that museum collections should be sold off and replaced by reproductions, his logic being that most people would not know the difference. Kinsley remarked that personally he “certainly couldn’t” tell the difference, and then went on to add his own smug ignorance to Banfield’s bottomless pit of philistinism by adding that fakes placed in the DIA would not even have to be good quality reproductions.

Kinsley claimed that “most people’s appreciation of art” comes from seeing “posters or postcards or beach towels or t-shirts,” and he concluded his piece of writing with the tongue in cheek intimation that the DIA’s masterworks could be replaced “secretly” by making “the switcheroo late one night.” Kinsley was being facetious of course, but his flippancy masked a barely concealed contempt for art and its enthusiasts. Kinsley neglected to mention that Edward Banfield was also opposed to the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts and that he was an advisor to Republican presidents Nixon, Ford, and Reagan. So much for liberalism.

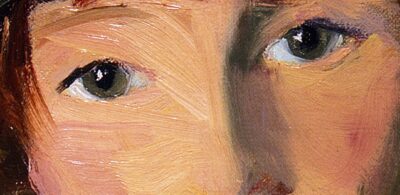

But there is a precedent to the boorish notions of Banfield and Kinsley. At the end of 1962 the Louvre in Paris loaned Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa to the U.S. government for exhibit in the United States. The painting was endlessly hyped by the media, resulting in a sort of frenzy, or what arts writer and social historian Robert Hughes came to call, the Mona Lisa Curse.

On January 8, 1963 the Mona Lisa went on view at the National Gallery in the nation’s capital; U.S. President John F. Kennedy, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson were in attendance. The painting itself was given Secret Service protection at the same level ordinarily given to presidents. On February 4, 1963, the Mona Lisa went on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where during a three and a half week run, over one million people shuffled by the celebrated oil painting. When hearing that the Mona Lisa was coming to America, Andy Warhol made the oafish wisecrack, “Why don’t they have someone copy it and send the copy, no one would know the difference.”

Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight apparently could not countenance Kinsley’s foolishness, and so fired a metaphorical “shot across the bow” at The New Republic’s editor-at-large titled, A suggestion to replace art with reproductions in bankrupt Detroit. Knight’s withering screed berated Kinsley for adding to the “rich tradition of know-nothings writing about art and museums,” and for advocating “Art for the aristocrats, reproductions for the peasants.”

Though I agreed with much of what Knight wrote, he concluded that Kinsley’s piece failed as satire because it labored under “the common misconception that art is for everyone, even though it isn’t. Art is not for everyone (that would be TV), it’s for anyone – which is not the same thing.” In those words I find an assessment as absurd as Kinsley’s. Knight contradicts himself by admonishing Kinsley for having an aristocratic view of art, then proceeds to express what is the quintessential patrician view of art – it is not for everyone.

I have no regard for the works of postmodern artist Tracey Emin, who I am told is one of Britain’s greatest living artists and a “leading light” in the circle of bloated art star frauds nicknamed the “Young British Artists.” But after she received the Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) at the investiture ceremony held on March 7, 2013 at Buckingham Palace in London, Emin said: “I think that art’s for everybody and everybody’s entitled to the best culture, the best literature, the best education, the best that everyone can have.” Emin, who has declared herself to be a royalist, voted for the Conservatives in the 2010 election, and accepted a commission from Tory Prime Minister David Cameron to create an installation piece for 10 Downing Street. She can proclaim that “art is for everybody,” but the art critic at the “liberal” L.A. Times declares the exact opposite. My goodness… the world has been turned upside down.

If “art is not for everyone” as Mr. Knight tells us, why then is it part of the core curriculum of the U.S. public education system? Should we stop teaching children about art? Art education in U.S. public schools has suffered brutal cutbacks for the last few decades, and Mr. Knight’s unhelpful proclamation only serves to place the finishing touches on its demise. My point is that we are not born with language and writing skills anymore than we have an inborn sophisticated appreciation of art and aesthetics… all of these things are obtained through education and socialization. If, for whatever reason, we stopped teaching children the use of language and writing, we would not have to wait long to see the harmful results. Curtailing or eliminating arts education in American schools will have no less a detrimental outcome.

Knight rebukes Kinsley for his “slide into phony populism” and then stakes out the anti-egalitarian position for himself by writing: “a great thing about democracy is that it aspires to create opportunities for anyone to become an elitist (….) That’s a primary reason we even have places like the Detroit Institute of Arts.” Actually no, the great thing about democracy is that it takes power from the hands of elites and places it in the hands of ordinary people, at least in theory it does. I do not call for the defense of the DIA because it helps to develop and maintain elitism, I support the museum because making a great collection of art accessible to everyday working people is a fundamental aspect of a democratic society.

Kinsley’s open contempt towards art and its aficionados, and Knight’s doggedness that “art is not for everyone” are both unwise if not laughable positions. I find them irksome because I have always believed and advocated that art is for everyone. I say this not as an activist, a trendy dilettante, an academic, or God forbid, a bourgeois art critic. I make the pronouncement as an artist who has been creating drawings, prints, and paintings his entire life.

A foundation of this conviction of mine is partly based upon seeing how art and culture has operated on a grass-roots level in the Mexican American community. “Making due with what you have” is a partial definition for “rasquache,” a Chicano term that describes an aesthetic of necessity and defiance. Rasquache sprang from poor barrios where working class people had few resources and even less access to art, at least how the dominant society defined art. Creating something out of nothing was rasquache, it was a “people’s art” made by those untrained in art, and it became a primary force in Chicano art and aesthetics.

In this short interview with Dr. Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, a foremost scholar of Chicano and U.S. Latino art, we are given a clear definition of rasquachismo and how it has shaped working class Chicano culture. Ybarra-Frausto makes clear that rasquache is not analogous to the kitsch or low-brow art of the postmodern “avant-garde.” Rasquache has a class dimension, it is rooted in poor Chicano communities and has always been a form of cultural resistance to the dominant society.

During the Chicano Arts Movement of the late 1960s, artists embraced rasquache and exalted the sleek modernist lines and intricate paint jobs of low-rider cars, the altars and religious icons of pious Catholics, the uniquely ornate placas (graffiti) found on the street, the attire of Cholos wearing button down flannel shirts with bandanas around their foreheads, the “Mom & Pop” storefronts painted in bright colors, the iconography of pre-Columbian civilizations and the Mexican Revolution, and so much more. Chicano artists were stirred by the life found in their communities, and they distilled that experience into a unique aesthetic. Those artistic sensibilities still largely imbue and guide contemporary Chicano art.

Rasquache is a word that once referred to things tawdry and cheap, but its meaning was changed in the late 60s to describe the assortment of visual cues, histories, and cultural identifiers that made up the new Chicano aesthetic. At the time there was an explosion of murals, theater pieces, and posters that were rooted in rasquache sensibilities, works that sought to uplift, beautify, defend, and unite the Mexican American community through art. This is something my friend and artistic associate Gilbert “Magú” Luján (RIP) discussed with me on more than a few occasions. Artists like Magú felt that art was for, and sprang from, the community. Mexican Americans have developed their art and culture from the ground up, nurturing and cultivating it even as it was denied a place in America’s cultural institutions. To Chicanos, Knight’s proclamation that “art is not for everyone” sounds not only ridiculous, but discriminatory.

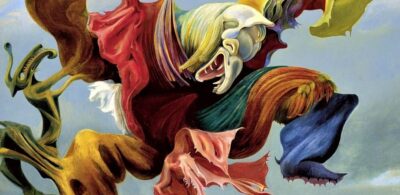

But there was another dimension to the Chicano Art Movement in the late 1960s. We were inspired by the likes of Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros of the Mexican Muralist School. Those artists created public works in the belief that art was for everyone, and that working people would be enriched by interactions with art. Though snubbed today by those who spout postmodern gobbledygook, that democratic impulse in art still survives.

I must remind the “art is not for everyone” crowd of the 1932 América Tropical mural created in Los Angeles by Siqueiros. Preserved in situ by the Getty Conservation Institute, the mural on L.A.’s downtown Olvera Street now has its own museum, which opened to the public in October, 2012 to great acclaim. América Tropical is one of L.A.’s finest historic examples of art being for everyone; it is a work that birthed a new phase in American muralism that eventually led to Los Angeles becoming the “mural capital of the world” by the early 1970s.

In some quarters art has become a cynical intellectual exercise that is incomprehensible without an art degree and knowledge in dubious and obscurest theories. Things are really much simpler; making and appreciating art is what makes us human. Art is but one facet of an ordered human community, it has always been so. If you want to know what mathematics are all about, you might want to ask a mathematician. If curious about the stars in the heavens, talk to an astronomer. It follows that if you want to know about art, you should ask an artist.

Leave the critics to argue amongst themselves.