Rigoberta Menchú, Gilberto Sánchez, & Ana Gatica

This article is about the barbarous assassination of a young Mexican artist, Gilberto Abundiz Sánchez. Why would unidentified armed men take an artist from his home and murder him? Considering the artist was just one of over 50 victims killed in one year in a single region, why are the authorities unable – or unwilling – to stop the killers? This is the reality of today’s Mexico, the subject of this piece. But this essay is also about much broader, international issues, human solidarity, and the democratic spirit.

Gilberto Abundiz Sánchez was a 30-year old artist attending the Popular Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Located in Michoacán, Mexico, the University is the oldest institution of higher education in the Americas.

By all accounts Sánchez was dedicated to art, he was a printmaker and painter. He was last seen watering the plants at his mother’s home when he was kidnapped on March 30, 2015. The remains of Sánchez were found on May 21, 2015 in Chilapa, Guerrero. He and two other young victims had been killed, dismembered, wrapped in blankets, and dumped along a roadside. The corpse was identified as Sánchez because of its unique tattoo.

The staff, students, and authorities of the University released a statement to express their “grief, anger, and outrage at the brutal murder of the student of the Bachelor of Visual Arts.” The collective statement describes Sánchez as a “peaceful, enthusiastic, and creative young man who actively participated in outreach activities that the Graphic Arts Department organized.”

The University communique also posed some very serious questions; “What happens in a country that allows the murder of its young students?” “Why do they fear the intelligence and creativity of young people, who represent the future of Mexico?” “Why has the whole society become a hostage to terror?”

The statement closed with these defiant words. “We are not willing to continue to act as if nothing happened in this country, that the death of Gilberto Abundiz Sánchez was natural and not the result of an undeclared war which has been unleashed against students, workers, peasants, and thinking people not aligned to power.”

The University statement is significant for two important reasons. It comes from the University staff, which includes academic as well as administrative faculty; it was also a collective statement issued in the name of the student body. More importantly, the bulletin expresses what millions of Mexicans are currently thinking about the criminal clique that rules their country.

Which brings us to the self-made controversy swirling around Rigoberta Menchú Tum, the indigenous Quiché woman, Guatemalan Human Rights activist, and 1992 Nobel Peace Prize winner. If anyone in the U.S. remembers Rigoberta Menchú Tum, it is as a heroic and altruistic “native rights” activist. After surviving the depredations of death squads in her homeland and the state murder of her family, after suffering insults and verbal muggings from reactionary critics aplenty, Menchú has managed to besmirch and defile her own legacy by collaborating with the authoritarian government of Mexico.

I once respected Rigoberta Menchú… that is no longer the case. The reasons for my bitter disappointment with Menchú are headline news in Mexico, but the calamity she has set off in Mexico has not been covered in the U.S. press. As a result I feel obligated to break this cheerless story to my fellow North Americans.

On May 26, 2015 Rigoberta Menchú was accredited by Mexico’s National Electoral Institute (INE), as an official electoral observer for the country’s June 7, 2015 midterm federal and state elections.

The INE paid Menchú $10,000 U.S. dollars to “promote voting and democracy” during her five-day stay in Mexico. According to information published in the Mexican press, Menchú charged $40,000 dollars for her visit, the balance being paid by private foundations. Here I must add, if Menchú has been paid by the Mexican government to lecture the people on democracy, and to be an election observer, can she really be seen as impartial?

Specifically, the INE is sending Menchú to the conflict ridden state of Guerrero to drum up support for the sham elections, but why Guerrero? Because that region is home to the Ayotzinapa teachers’ training college that had 43 of its students kidnapped by police and their drug gang accomplices. Ayotzinapa has become the political lightning rod of the nation, a democratic prairie fire has sprung from the tragedy, and President Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) hopes to stamp it out.

It should be remembered that when the police of Guerrero seized the 43 Ayotzinapa students on Sept. 26, 2014, they turned them over to the Guerreros Unidos (United Warriors) drug gang to be murdered. There is no clearer evidence of the seamless relationship that exists between vast sectors of the Mexican government and powerful drug syndicates.

Lorenzo Córdova, president of the National Electoral Institute, presented Menchú with her accreditation at a photo-op press conference held at the INE headquarters. Córdova said Menchú was “a woman recognized internationally for her relentless struggle for the defense of the rights of indigenous peoples and for her convictions concerning peace.” It was a stunning bit of propaganda since just days earlier the Indigenous Council of Guanajuato filed a complaint against Córdova with Mexico’s National Commission on Human Rights. During a phone conversation between the president of the INE and the group’s executive secretary, Córdova made racist jokes that ridiculed the way indigenous people speak.

Does Menchú not see that publicly accepting accreditation and money from Lorenzo Córdova legitimizes his image? If she was unaware of the controversy surrounding Córdova, then maybe she is not cognizant of other Mexican government intrigues. I suppose calling her naive is the best defense that can be offered, but callowness is not an attribute an election observer should possess.

Córdova’s phone call was surreptitiously recorded and released on Spanish language social media, where it has circulated ever since. Because of this Córdova “apologized” for his “unfortunate and disrespectful” jokes, but the INE asked the Attorney General’s Office to mount an investigation into who secretly recorded the conversation and made it public.

The former Attorney General, Jesús Murillo Karam (affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) was widely criticized for attempting to cover-up the truth regarding the Ayotzinapa 43 kidnapping. He infuriated millions when at a press conference he was questioned regarding the 43 missing students, and responded with “that’s enough, I’m tired” before walking away from the press. The pro-Democracy movement then used Karam’s words #YaMeCanse (I am tired) in a social media campaign to show their contempt for government violence and impunity. Karam resigned in Feb. 2015, but the new Attorney General, Arely Gómez González (also affiliated to the PRI), will most likely lack the energy to tackle the Ayotzi 43 case, but I think she will show great zeal in exposing and prosecuting those who recorded Lorenzo Córdova’s racist phone conversation!

But back to Menchú and her disingenuous but well paid “This is what democracy looks like” side show. On May 29, 2015, at a large public gathering organized by the INE at the International Center in Acapulco, Guerrero, Menchú delivered a lecture titled Democracy and the Culture of Peace, a talk that many across Mexico found offensive and insulting.

Broad sectors of the population in Mexico are frustrated by narco-politica (narco-politics); millions believe their votes have no power to effect change. They believe, for good reason, that oligarchs and drug lords have an absolute grip on power, nullifying the democratic process. They believe there is no official mechanism that can be used to implement the people’s political will.

Furthermore, the movement for democracy that sprang up around Ayotzinapa has called for a boycott of the elections; it is a strategy that presses for the abolishment of Narco-regime governance and an end to kidnapping and murder by the state. The demand is that the 43 be returned, and if that is not possible, all of the conspirators who kidnapped and murdered them be brought to justice. Who is Rigoberta Menchú to tell the Mexican people that their assessment of the situation is incorrect?

During her lecture Menchú told the parents of the missing 43 Ayotzinapa students; “I would urge the families to try to explain the reason” for their children’s “actions” prior to being kidnapped (as if the students shared blame for being taken hostage). Menchú told the parents to do so “without hiding the truth, because the truth dignifies us all,” a statement that implied the parents of the 43 missing students had lied in their campaign to pressure the government.

Menchú went on to say that “the vote is a personal decision,” and that an election “is an opportunity to renew authorities.” She asked the parents of the 43 Ayotzinapa students to never forget their children (as if they would!), and to go out and vote, because “Gentlemen vote, and that is my message.”

At the close of her address, Menchú asked for a moment of silence for the 43 missing Ayotzinapa students. After the awkward silence there was a question and answer period, and a 27-year old woman, Ana Gatica, took the stage to deliver what turned out to be a rather fiery public rebuke; Ms. Gatica is an indigenous Nahua from Guerrero.

Shaking with emotion and choking back her tears, Ms. Gatica addressed the honored guest as Hermana Menchú (Sister Menchú), “I do not know how you can ask us to make a vow to vote,” she said, when disappearances and murders of civilians go unpunished. Ms. Gatica pointed out that 50 young people living in the state of Guerrero have been killed between October 26, 2012 and May 30, 2015. The first to disappear “was the daughter of a cousin, Gabriela Itzel Ortiz Vazquez, 15, the last to be killed was Gilberto Abundiz Sánchez.” Gatica began to cry when she spoke of Sánchez, her friend and fellow graphic artist.

Ana Gatica pointedly stated: “Ms. Menchú, the indignation and anger cannot be finished, and I know you understand. One more thing, we cannot keep asking for a minute of silence for the missing, because asking for a minute of silence for each of the disappeared – and for everyone murdered in our country, in our state, means that we will remain silent forever.”

The comments of the brave and courageous Ana Gatica were captured in several Spanish language videos of the Democracia y cultura de la paz conference. Ms. Gatica received a stirring round of applause for confronting Menchú, it was no doubt more enthusiastic and heartfelt than the polite clapping given to Menchú at the close of her speech.

The day after Rigoberta Menchú’s speech, Felipe de la Cruz, a spokesman for the parents of the missing 43 Ayotzinapa students, deplored the conduct of Menchú. He said that she “fell into the INE game of promoting the elections,” and that she “does not know how they have governed us in Mexico for many years.” De la Cruz had some words of advice for Menchú, “If you want the truth, ask those who are paying you to making your comments.”

In 1982 Rigoberta Menchú rose to international fame with the release of her book I, Rigoberta Menchú. It told the story of the impoverished Quiché people living under the boot of Guatemala’s oligarchical landlords and their armed goons. Menchú’s family became involved in the land reform movement, and so became targets of the regime. Her father Vicente was arrested and tortured, her brother was executed by government soldiers, her mother was arrested, raped, and killed by government troops, and ultimately her father was burned to death in the 1980 Spanish Embassy Massacre. In 1981 Rigoberta Menchú fled Guatemala for Mexico and then France.

While in France Menchú met Elizabeth Burgos-Debray, who not only convinced Menchú to write her memoirs, but became the ghostwriter for the book. At the time I found the autobiography to be totally convincing, the tome fed the international solidarity movement that was determined to end the butchery in Central America. For the events detailed in her book, Menchú received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992.

Doubts about Menchú finally began to rise in 1999 when anthropologist David Stoll published Rigoberta Menchú and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans, a book that pointed out discrepancies and inaccuracies in Menchú’s autobiography. The left-wing – myself included – dismissed Stoll’s book, but Menchú’s recent skullduggery forces a reconsideration.

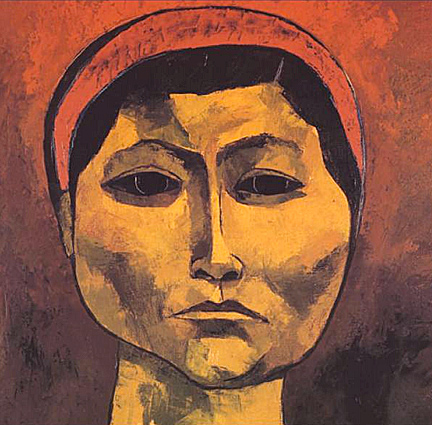

In 2009 I attended Guayasamín: Rage & Redemption, an exhibit at the Museum of Latin American Art (MoLAA) in Long Beach, California. It was a retrospective of artworks by the Ecuadoran master painter, Oswaldo Guayasamín (1919-1999). Prominently displayed was the artist’s oil on canvas portrait of Rigoberta Menchú. Guayasamín, a social realist artist and a man of the left, would no doubt be outraged over the shameful antics of Menchú.

It should go without saying that I no longer support Rigoberta Menchú, who has become but a faded image of her former self. No, I stand with Ana Gatica, the spirited and outspoken indigenous Nahua from Guerrero who knows how to stand for the people’s rights.