Robert Henri’s California

“Art cannot be separated from life. It is the expression of the greatest need of which life is capable, and we value art not because of the skilled product, but because of its revelation of a life’s experience.” – Robert Henri

Robert Henri’s California: Realism, Race, and Region, 1914-1925, is a small but important exhibition at the Laguna Art Museum in the sunny coastal city of Laguna, California. Running from Feb. 22 to May 31, 2015, this exceptional show focuses on the paintings that Henri (pronounced ‘hen rye’) created while visiting the southern Californian cities of San Diego and Los Angeles from 1914 to 1925.

I had hoped to take some extreme close-up shots of the paintings, but the Laguna Art Museum does not allow photography of any kind in the Robert Henri’s California exhibition. Fortunately the museum agreed to provide me with some .jpg reproductions of art from the exhibit, which serve as illustrations to this article.

In 2007 I mentioned Henri at the end of my article, Bouguereau & His American Students, which told of Henri being a student of the academic painter William Bouguereau and his inevitable break with academic painting.

In 2008 I published a second article, Apostles of Ugliness – 100 Years Later, in which I described the “Ashcan School,” the first art movement in the U.S. that Henri played a major part in founding. The Ashcan group were the original social realist painters of America, given to depicting the lives of the poor and everyday working people.

Robert Henri’s California dazzles on several fronts. It awes the viewer with Henri’s skill as a painter and brings to life craft as an essential part of painting. It produces a sense of admiration regarding Henri’s ability to capture the essence of people in formal portraiture, revealing the deep humanism Henri possessed. The exhibit also affirms something little known about the man usually thought of as a “New York” realist painter – his deep and abiding love for the lands and people of southern California.

Henri first came to San Diego in June of 1914, and lived in a cottage above the magnificent sun drenched La Jolla Cove. He helped Alice Klauber, a former art student of his living in San Diego, to plan a fine art program for the upcoming 1915 Panama-California Exposition. Henri arranged the Modern American Art exhibit, a display of paintings by Ashcan artists that was shown at the Exposition’s Fine Arts Building.

His own works were exhibited along with canvasses by George Bellows, John Sloan, William Glackens, and other artists now considered to be masters from the period. Of the nearly 50 paintings displayed, not a single one sold. Nonetheless, the Exposition was an event that would have considerable impact on the life and work of Henri.

While Henri lived in California he forsook painting portraits of high society, and instead painted lush and emotive portraits of the people ordinarily kept at arm’s length by the dominant white culture; Mexicans, Mexican Americans, Chinese immigrants, and African Americans.

He also first painted indigenous people while in California, creating portraits of artisans from the New Mexico San Ildefonso Pueblo that he befriended at the 1915 Panama-California Exposition. I found these glorious canvasses of indigenous people to be breathtaking examples of the painter’s craft, and for me they were the core of the exhibition.

The Native Americans recreated a Pueblo village at the Panama-California Exposition, what the exposition named “The Painted Desert.” It was an attraction where indigenous people could share their culture, as well as create and sell traditional arts and crafts. Henri was so impressed by the people of the San Ildefonso Pueblo, that in later years he would visit New Mexico and create a large body of extraordinary Native American portraits.

Henri’s paintings of Chinese immigrants on view at the Laguna Art Museum are dazzling in their own right, especially the exquisite canvas of a young girl named Tam Gan. Painted in 1914, the portrait is created with rapid, paint loaded brushes over an underpainting of burnt sienna and ochre. Technically it is like all of the other Henri oil paintings – a radiant masterwork, but there is an unseen political aspect to the painting that makes it out of the ordinary, and that fact is most likely missed by all except for those familiar with American history.

Henri’s painting of the lovely Tam Gan was made when the Chinese Exclusion Act was strictly enforced by the U.S. federal government. The law was first enacted in 1882 for the express purpose of prohibiting all Chinese workers from entering the United States. The exclusionary law strictly curtailed immigration from China and prohibited Chinese from becoming U.S. citizens. The law did not apply to Chinese travelers, merchants, teachers, and students, but all those who were exempt had to present to U.S. authorities a certificate from the Chinese government stating they were not workers.

The Exclusion Act specifically targeted Chinese females. Eligibility to enter the U.S. was based upon marital status; if a woman was not married she was considered a worker (or a prostitute) and denied entry. If a woman was a laborer she was barred from entering the U.S., if she was not a worker but married to one, she was still banned. Only a wealthy merchant’s wife was able to gain entry to the U.S. The government strategy was simple, without women there would be no children, and the radical reduction of the Chinese population in America would be achieved.

The Exclusion Act was made permanent in 1902. The Chinese had few friends in the U.S. at the time. Twelve years after the Exclusion Act was made permanent, Henri would defiantly paint portraits of the Chinese living in and around San Diego.

The Chinese Exclusion Act would not be repealed until 1943, and even then the U.S. Congress allowed only 103 Chinese people to enter the U.S. per year, a law that was overturned in 1965.

Painting portraits of the underclass is what one would expect from the leader of the Ashcan School. But Henri’s interest in the poor and the dispossessed was not a mere bourgeois affectation. In 1915 Henri wrote an essay titled My People that was published in The Craftsman, a journal that promoted arts philosophy and the Arts and Crafts movement. The think piece reveals a large minded take on the world. Henri was a forward thinking man, hard to pin down politically, but one could say he was a free thinker. He met and admired the anarchist activist Emma Goldman, and even painted her portrait in 1915. In My People Henri stated:

“The people I like to paint are ‘my people,’ whoever they may be, wherever they may exist, the people through whom dignity of life is manifest, that is, who are in some way expressing themselves naturally along the lines Nature intended for them. My people may be old or young, rich or poor, I may speak their language or I may communicate with them only be gestures.” In that same essay Henri went on to say:

“I find as I go out, from one land to another seeking ‘my people,’ that I have none of that cruel, fearful possession known as patriotism; no blind intense devotion for an institution that has stiffened in chains of its own making. My love of mankind is individual, not national, and always I find the race expressed in the individual.

And so I am ‘patriotic’ only about what I admire, and my devotion to humanity burns up as brightly for Europe as for America; it flares up as swiftly for Mexico if I am painting the peon there; it warms toward the bull-fighter in Spain, if, in spite of its cruelty, there is that element in his art which I find beautiful, it intensifies before the Irish peasant whose love, poetry, simplicity and humor have enriched my existence, just as completely as though each of these people were of my own country and my own hearthstone.”

Since Henri could so eloquently put forth his philosophy on art and life, I will close this review with an excerpt from his 1923 The Art Spirit. It was a book that summed up his views regarding art, combining transcribed lectures given to his students, with critical commentary and musings on life and aesthetics. I have long held his words to heart, and feel they should be read and understood by any aspiring artist. The following is perhaps more relevant today than it was in 1923:

“We are living in a strange civilization. Our minds and souls are so overlaid with fear, with artificiality, that often we do not recognize beauty. It is this fear, this lack of direct vision of truth that brings about all the disaster the world holds, and how little opportunity we give any people for casting off fear, for living simply and naturally. When they do, first of all we fear them, then we condemn them. It is only if they are great enough to outlive our condemnation that we accept them.

Always we would try to tie down the great to our little nationalism; whereas every great artist is a man who has freed himself from his family, his nation, his race. Every man who has shown the world the way to beauty, to true culture, has been a rebel, a ‘universal’ without patriotism, without home, who has found his people everywhere, a man whom all the world recognizes, accepts, whether he speaks through music, painting, words, or form.”

________________

Addendum:

While visiting the Detroit Institute of Arts in May, I noticed a painting by Henri in the museum’s extensive collection.

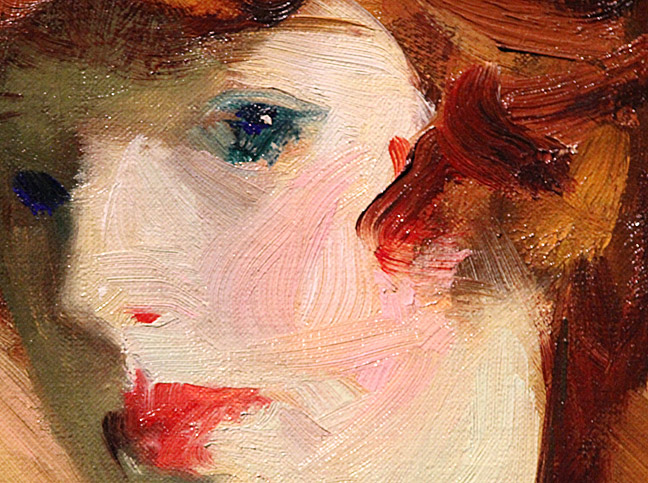

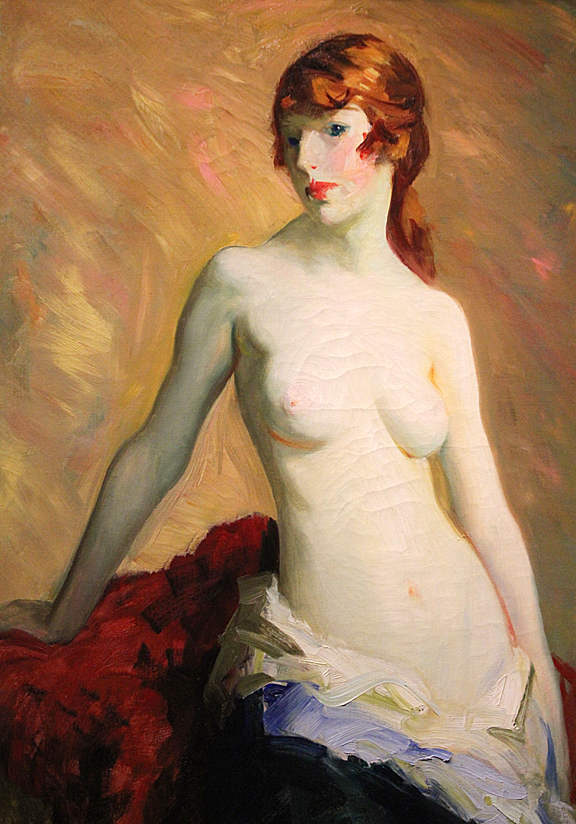

Painted in 1915 and titled The Young Girl, it is a superlative example of how Henri painted with bold, energetic brush strokes laden with explosive color.

In 2005 David Gordon, the Director of the Milwaukee Art Museum, said the following about the painting:

“Henri encouraged the painting of life as it really was and this three-quarter body nude of 1907 was so striking in its realism that Mrs. Henri took an advertisement in the newspapers to tell the world that it was not her that posed for her husband. The model, Edna Smith, is simply gorgeous and we have used her face as one of the emblems of the Museum. To have used the rest of her would still have shocked 97 years later.”

Because the oil on canvas painting was created in the same time frame as those exhibited at the Laguna Art Museum, I am including details of The Young Girl as an added example of Henri’s prodigious talents.