Sept. 11, Chicano Park & Chile

On Sept. 7, 2013, I went to the Southern California coastal City of San Diego, where I revisited the famed Chicano Park murals located in the Mexican-American community of Logan Heights. I spent a day photographing the park’s huge murals that are painted on the monolithic pillars of a freeway overpass, and in months to come I intend to present photos of the wall paintings along with essays on the how’s and why’s of their creation. But this post is more than a “sneak peak” at the photos. Sept. 11, 2013 marks the 40th anniversary of the Chilean coup, and this article will focus on one particular mural in Chicano Park titled, Tribute to Allende.

Eleven Minutes, Nine Seconds, One Image: September 11 was an independent film on the subject of the al-Qaeda terror attacks that targeted Americans on Sept. 11, 2001. The movie was actually 11 different visualizations of those events, as told by 11 directors from around the world; the film won two awards at the Venice Film Festival when it premiered in 2002. The contribution to the movie from U.K. director Ken Loach focused on a Chilean folk singer named Pablo. Exiled in London as a result of the coup d’état that took place in Chile on Sept. 11, 1973, Pablo is filmed writing a letter to the American people expressing his sorrow over the 9/11 attacks. He also explains that “enemies of freedom” ravaged and bloodied Chile on 9/11/73. This sets the tone for the rest of my article.

On April 22, 1970, working class Mexican-Americans living in Logan Heights discovered that a parking lot for the Highway Patrol was being constructed in an open area beneath the just built Coronado Bridge. Already stinging from poverty, racism, police brutality, and the displacement of 5,000 families and their homes due to the construction of the Interstate 5 eight lane freeway and the Coronado Bridge, the community had had enough. The Chicanos of Logan Heights seized the land, stopped the bulldozers, drove off the construction workers, and began to build a park for their district. Activists wanted a “people’s park”, and demanded that the land become a liberated zone where Chicano art and culture could flourish. The police arrived in great numbers and a standoff over the park lasted for twelve days. Finally the city agreed to acquire the land for the development of a community park. On January 1, 2013, the National Park Service placed Chicano Park on its Register of Historic Places.

I was seventeen-years-old in 1970, and I had been following news of the Chilean revolution in America’s underground radical press. I do not recall how I got a copy of Por Vietnam, the 1968 album released by the Chilean group Quilapayún, but it changed my life. I had already heard of Victor Jara and Nueva Canción Chilena, so it was the work of Chile’s artists that made me pay closer attention to what was happening in their country. Of course, there was turmoil everywhere in 1970, and El Movimiento (the Chicano Movement) was at its height in California. The anti-Vietnam war Chicano Moratorium march and rally would take place in East Los Angeles on August 29, 1970, and at seventeen I was very much involved in the spirit of the day.

Through the Chicano and antiwar movements I learned that young muralistas in Chile like the Brigada Venceremos, Brigada Ramona Parra (BRP), and other collectives were painting vibrant political murals. I learned that David Alfaro Siqueiros went to Chile in 1941 to paint his influential mural, Muerte al Invasor (Death to the Invader) in the southern Chilean town of Chillán. The mural was painted during a time of political crisis in Chile; during a 1946 general strike in support of striking miners, government soldiers killed six protesting workers, including a 20 year old activist named Ramona Parra – the BRP’s namesake. From afar I watched in abject horror as Chile was drowned in blood on Sept. 11, 1973.

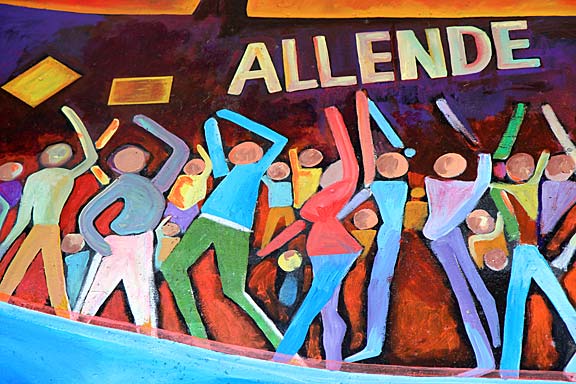

I believe the earliest mural in Chicano Park was the 1973 Historical Mural, a panorama of events and heroes important to Chicanos. Along with muralist Victor Ochoa and a collective of others, L.A.’s own Gilbert “Magú” Luján (1940-2011) lent a hand in creating the painting. Dozens of mural works followed over the years, and some of these will be pictured in future posts. Tribute to Allende was painted in 1974 by Smiley Benavides & Team from Los Angeles, showing once more how Chicano Park served as a lightning rod for Mexican-Americans throughout the Southwest. Like many of the murals in Chicano Park, Tribute to Allende was fully restored and preserved in 2012 as a result of The Chicano Park Mural Restoration Project. The artists who restored the mural are Norma Montoya, Guillermo Rosette, and Mario Torero.

I consider Tribute to Allende to be one of the finest mural works in Chicano Park. Many of the park’s murals were created by teams of non-professional artists, but while some of the murals might be lacking in artistic excellence, they all excel when it comes to expressing meaning, community spirit, and the zeal for creating a new society. Tribute to Allende was obviously created by skilled artists; Internationalist in flavor, the mural transcends Chicanismo to address larger issues and the world community. Aesthetically it takes its cue from the militant Chilean murals of the Allende years, capturing the energy of a people struggling against tyranny and oppression. Like a number of Chicano Park murals, Tribute to Allende is wrapped around a massive concrete column that holds up the freeway, so the artists took advantage of the architectural support and made their work three dimensional. Almost abstract, the mural’s nearly Day-Glo colors positively glow in the Southern California sun.

In the early morning hours of September 11, 1973, the armed forces of Chile carried out a coup d’état against the democratically elected Socialist government of President Salvador Allende. Within a few hours the military controlled the entire country with the exception of Santiago, the nation’s capital. President Allende and his loyal bodyguards were surrounded inside La Moneda, the presidential palace; Allende was defiant and refused to surrender to the military. The Air Force bombed La Moneda, hitting it with at least 17 bombs. The generals say Allende took his own life, but it was the military that murdered Chilean democracy.

What followed was a military dictatorship that reigned until 1990. Led by General Augusto Pinochet, the regime outright murdered some 3,200 people and arrested well over 130,000. Sports stadiums were used as prisons and “interrogation” centers. At the time of the coup, Santiago’s Estadio Nacional (National Stadium) held over 40,000 detainees. At the Estadio Chile (Chile Stadium) in Santiago, thousands were held by the Army, including the pro-Allende folk singer Victor Jara. Recognizing the popular singer, soldiers pulled out his fingernails and smashed his hands with rifle butts, then mocked him by requesting that he play them a song on guitar. The soldiers shot Jara in the back of the head, then raked his body with machine gun fire.

Over the years, thousands of people became desaparecidos (the disappeared), kidnapped by security forces and never seen again. Tens of thousands more were sent to detention camps where they suffered beatings, rape, and torture. The regime created the Caravana de la Muerte (Caravan of Death), an Army death squad that rounded up and assassinated dozens of political opponents. All this and more… the entire country of Chile had become a torture center.

As it turned out, the Nixon administration had long plotted to overthrow the government of President Salvador Allende, who had committed the unpardonable crime of nationalizing Chile’s resources. Up until the Allende administration, Chile’s three largest copper mines were owned by two U.S. companies, Anaconda Copper Company and Kennecott Copper Corporation. On July 11, 1971, President Allende’s proposed constitutional amendment allowing nationalization of Chile’s copper mines passed the Congress by unanimous vote. The U.S. plot against Chile went into high gear.

Declassified U.S. documents show that the White House and the CIA played a direct role in the overthrow of the Allende government. In 1970 President Richard Nixon gave the CIA orders to “make the economy scream” so as to “prevent Allende from coming to power or to unseat him.” A 1970 memo written by the CIA deputy director of plans stated: “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup. It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that the USG (the U.S. government) and American hand be well hidden.” On June 27, 1970, Henry Kissinger, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, infamously remarked, “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist because of the irresponsibility of its own people.”

On Sept. 10, 2013, it was announced that Victor Jara’s family succeeded in serving a civil lawsuit to the former Chilean Army officer allegedly responsible for ordering Jara’s murder. The former officer, Pedro Barrientos Nuñez, was found living comfortably in Florida, enjoying U.S. citizenship through marriage to an American woman. In December 2012 a Chilean court charged Nuñez in absentia for the brutal murder of Jara… Nuñez had fled to the U.S. in 1989. The lawsuit brings seven claims against the ex-commander, including crimes against humanity, torture, and extrajudicial killing. It is a welcome break in the nightmare legacy of the Pinochet coup, but after 40 years, justice has still not been served. The affair however does make the Tribute to Allende mural as relevant today as it was in 1974.

The young artists that created the murals in the Logan Heights Barrio, painted their spiritual, political, international, and Chicano visions onto the walls for all to see. Those murals continue to be a great source of community pride, moreover, they stand as examples of an authentic “people’s art,” the very antithesis of today’s detached, elite, postmodern art. Rather than being frozen in the past, the Chicano Park murals embody a way forward for today’s artists.