Diego Rivera mural blocked from public view!

This is an Open Letter to the Students and Faculty of the San Francisco Art Institute.

In September 2011, it was a real pleasure to travel to San Francisco for the express purpose of photographing the Great Depression era murals that exist in the city. I visited the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), where I made photographic studies of Diego Rivera’s The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City, located in the campus gallery named after him.

Rivera’s mural is a brilliant tromp-l’oeil, showing us a mural within a mural, with Rivera and assistants on a scaffold as they paint a monumental worker representing the working class; in the artist’s words, a “Gigantic worker, his gaze fixed firmly forward.”

A number of foreign visitors were among the U.S. tourists in the gallery that day; I was impressed by their silent contemplation of the mural. Indeed, the painting is a major destination for cultural tourism, and many travel guides for San Francisco suggest a visit to the SFAI for a look at Rivera’s mural.

Wanting to share my passion for Rivera’s work, I uploaded a few of my photos of his SFAI mural to my web log in 2011, along with some of the history behind the making of the fresco. I might add that I traveled to the Detroit Institute of the Arts (DIA) in May of 2015, not just to see that museum’s Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit exhibit, but to study and photograph Rivera’s magnificent Detroit Industry mural cycle painted in an internal courtyard of the DIA. Throngs of people jammed the museum for the Rivera and Kahlo exhibit, which by the end of its run was seen by well over 153,000 people, making it one of the biggest shows in the DIA’s history.

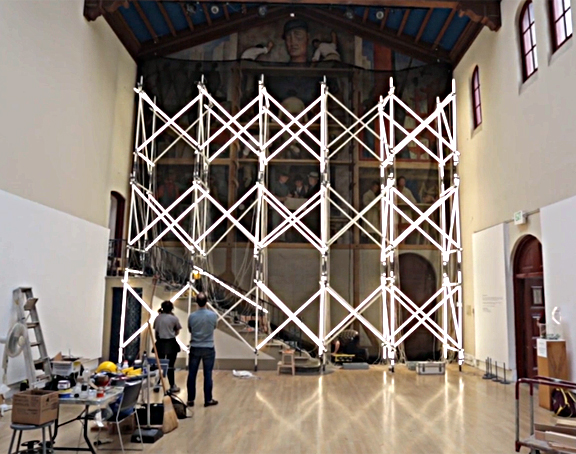

As a working painter and printmaker in Los Angeles, I write this open letter on the subject of Change the World or Go Home, an installation of scaffolding and fluorescent lighting by Mexico City-based artist Alejandro Almanza Pereda, now on exhibit in the SFAI’s Diego Rivera Gallery. I write to express my dismay that Mr. Pereda’s installation unnecessarily blocks public viewing of Diego Rivera’s 1931 mural, The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City. I also have misgivings about Pereda’s installation being placed so close to Rivera’s delicate fresco mural; I believe it poses a threat to the mural’s preservation. More to the point, I hope to explain why I believe that Pereda and the SFAI have denigrated the legacy of Rivera and his fresco mural.

Mr. Pereda is an artist in residence at the SFAI, and so was given a solo exhibit in the Diego Rivera Gallery. Pereda has constructed 24-foot-high scaffold, with a jumble of functioning fluorescent light tubes replacing the scaffold’s wood or steel planks. In the SFAI’s promotional material for Pereda’s scaffold, the school writes some typical postmodern gobbledygook that the fluorescent light tubes are meant to “contend with and complicate the legacy and monumentality of Diego Rivera’s fresco.” But what art institution does not know that light, even in limited amounts, can cause cumulative and irreversible damage to works of art?

Art conservators should be apprehensive that Rivera’s fresco is now exposed to light thrown from Pereda’s giant fluorescent light fixture. Fluorescent light contains high levels of UV radiation, and museums use strict guidelines to prevent artworks in their collections from being unnecessarily exposed to the dangers of UV light.

A short film made under the auspices of the SFAI, shows Pereda’s scaffold and fluorescent light fixture being built with the help of young assistants. Black construction netting was initially erected, supposedly to protect the mural while the scaffold was built. A heavy mechanical lift was used in the construction process, and upon completion the scaffold was improbably secured in place with wires anchored to the walls of the gallery. There appear to be no professional technicians involved in the work, nor art conservators to condition-check the mural. The finished scaffold looks flimsy. With San Francisco sitting on the San Andreas Fault and six other significant earthquake fault zones, there is good reason to be anxious.

I am appalled that the SFAI allowed Pereda’s scaffold to be placed so close to a priceless art treasure, not to mention exposing it to UV light. I can think of no other legitimate art institution that would so recklessly endanger an important internationally recognized work in their collection. I cannot imagine the Detroit Institute of the Arts allowing such a cheap stunt to be pulled off anywhere near their Detroit Industry murals.

Pereda apparently believes that the art and legacy of Diego Rivera is a “limiting screen,” a curtain that restrains Mexican art and confines Mexican artists. Pereda envisions his scaffold as a different sort of screen with which to see the world through. The luminous glow from the fluorescent bulbs makes it impossible to view or photograph Rivera’s fresco! The scaffold itself, even with its lights turned off, impairs a clear view of Rivera’s mural. Evidently the SFAI is titillated by Pereda’s art prank masquerading as profound artistic exploration. In the aforementioned film, Pereda attempted to explain the meaning of his scaffold installation:

“I always had kind of trouble with Mexican Muralism. The Mexican government supported Mexican Muralism, and so that more or less it became a type of propaganda. So when I see the murals, sometimes, you know, like the one here… it’s about progress, the scaffolding symbolizes progress. But a different progress, like destruction, you create something new, like a new condo over a really nice house. And that’s changing the face of the cities, so sometimes it’s terrifying to see scaffolding.”

In the quote above Mr. Pereda spouts utter nonsense. He implies that Diego Rivera and his fellow muralists, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, et al., were propagandists for the Mexican government, which could not be further from the truth. The majority of the muralistas were political radicals, and they often publicly clashed with the government over a variety of issues. In 1922 Rivera and other important artists founded the Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, a group dedicated to creating revolutionary art. David Alfaro Siqueiros wrote the group’s manifesto.

That same year, Rivera, Siqueiros, and many other artists joined the Mexican Communist Party (Frida Kahlo would join in 1928). Rivera’s membership in the party put him in direct odds with the government, which banned the party and its activities in 1925; the outright ban continued until the left-leaning Lázaro Cárdenas was elected president of Mexico in 1934. Anyone with even a cursory familiarity with the history of the Mexican Muralist Movement should know these facts. Perhaps Mr Pereda should go back to art school, oh wait… he is an artist in residence at the SFAI.

It seems that Mr. Pereda’s logorrheic style of babbling was a bit thin as an artist’s statement, so the SFAI graciously assisted with some of its own postmodern prose. The school’s promotional material for Pereda describes Rivera’s mural in the following words:

“Meanwhile, in SFAI’s Diego Rivera Gallery, we have been looking at Diego Rivera’s ass for 84 years. Of course, this was the artist’s intention. Rivera’s iconic work The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City (1931) offers an epic image of the reconstruction of San Francisco, depicting laborers and fresco painters alongside the patron, on the scaffold, and closest to our eye: the artist’s high-waisted rear.”

Looking at Rivera’s ass for 84 years? It was Rivera’s intention to show his “high-waisted rear” to the public? Excuse the Pop culture reference, but the SFAI’s brassy remarks remind me of an aside from British comedian John Cleese; “It’s all about backsides with you Americans, isn’t it.”

It is interesting that the SFAI’s mocking reference to “Rivera’s ass,” is the same type of derisive scorn heaped upon Rivera and his mural by critics in 1931. In his book, Painting on the Left: Diego Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco’s Public Murals, author Anthony W. Lee mentioned how reactionaries bashed the mural by accusing Rivera of having painted a portrait of himself defecating on his patrons! A less vulgar “critique,” but one no less spiteful, was made at the time by Kenneth Callahan, the painter from the state of Washington. Castigating the mural, he mentioned Rivera’s “flat rear, hanging over the scaffolding in the center. Many San Franciscans chose to see in this gesture a direct insult, premeditated, as indeed it appears to be. If it is a joke, it is a rather amusing one, but in bad taste.”

The only “ass” to be found in this story is the one who seeks to poke Rivera’s legacy full of holes.

Rivera intended his murals to be accessible to the public; that was the central tenet of the Mexican Muralist Movement to which he belonged. Many San Francisco Bay Area artists met and worked with him when he visited San Francisco, and it is because of his influence that San Francisco became a city full of murals. The evidence is everywhere, from the 1934 Chapel Mural painted at the Presidio by Victor Arnautoff, to the magnificent 1934 Coit Tower frescos at Telegraph Hill. From the 1936 San Francisco Life frescos by Lucien Ladaudt at the Beach Chalet restaurant, to the 1941-1948 History of California murals by Anton Refregier at the Rincon Center. Rivera made enormous contributions to art, and his legacy is not a “screen” that oppresses anyone.

While the San Francisco Art Institute does not publish Diego Rivera’s own words regarding the true intentions of his mural, I will happily do so. In his autobiography My Art, My Life, Rivera described the intent behind his 23-by-30-foot mural. Rivera wrote that he wanted:

“to present a dynamic concerto of construction – technicians, planners, and artists working together to create a modern building (….). I showed how a mural is actually painted: the tiered scaffold, the assistants plastering, sketching, and painting; myself resting at midpoint; and the actual mural subject, a worker whose hand is turning a valve so placed as to seem part of a mechanism of the building.

Since I was facing and leaning toward my work, the portrait of myself was a rear view with my buttocks protruding over the edge of the scaffold. Some persons took this as a deliberate expression of contempt for my American hosts and raised a clamor. However, I insisted that my painting meant nothing else than what it pictured. I would never think of insulting the people of a city I had come to love and in which I had been continuously happy.”

If you type in the title of Rivera’s mural on Google – The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City – you will find that the SFAI web page on the painting is the first item to come up, but this article on the mural is also listed. Over the years thousands of people from around the world have read my article on Rivera’s mural. It would be an understatement to say that I would have been upset if I had journeyed to the SFAI to study and photograph Rivera’s fresco, only to find the school had blocked the mural from public view by installing a scaffold made of fluorescent light bulbs in front of it.

The annoyance would have been made all the worse with the SFAI promoting the installation on an equal footing with Rivera’s mural. Since Pereda’s scaffold will block the view of Rivera’s mural until December 3, 2015, there will be many people who are going to be angry over being denied the pleasure of contemplating one of San Francisco’s greatest mural works.

You may choose to call the deliberate blocking of someone’s view of an artwork a clever act of “art intervention” or a means to “contend with and complicate the legacy and monumentality” of the artwork… but an honest person would call it censorship.

There is a larger cautionary tale to be told here regarding Rivera’s mural, one that has it roots in the history of the SFAI, but also in the chronicles of U.S. art and politics.

In 1931 Diego Rivera painted his mural at the SFAI, then known as the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA). Douglas McAgy was the school’s director from 1945 to 1950, and he transformed the institution into a center for the non-objective school of abstract art. McAgy hired abstract artists like Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, and Richard Diebenkorn as instructors, and tirelessly promoted abstract art through exhibitions and forums. To McAgy, figurative realism in art was passé and on its way out.

The “enlightened” McAgy was so offended by Rivera’s social realist mural that in 1945 he had a wall constructed over the fresco to prevent the public from ever seeing it [1]. While history has noted the total destruction of Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural at New York’s Rockefeller Center by the order of Nelson Rockefeller in 1934, the censorship of Rivera’s mural at the CSFA is barely known or acknowledged. In retrospect the suppression of the mural by McAgy has been forgiven by those who simply think the school director acted as an overzealous apostle of abstract art. As if that is an excuse for his blatant act of censorship.

But here is the delightful irony in this whole messy affair. Just as the director of the CSFA revamped the school into a citadel of abstract art on the West coast, putting the kibosh on figurative realism in the process, so too has the current leadership of the SFAI turned the school into a bulwark for today’s oh so fashionable postmodern art. As Shakespeare wrote in The Tempest, “What’s past is prologue.” Douglas McAgy covered Rivera’s mural in an open act of censorship; the SFAI covers Rivera’s mural and justifies it in the name of “ambitious new works.”

But I do not believe for a moment that McAgy’s censorship of Rivera’s mural was an act solely based on an extreme bias against realism in art. McAgy acted in full accord with the “Red Scare” that had seized control of US national politics.

In 1938 the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) attacked Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Work Progress Administration (WPA). Specifically, HUAC went after the WPA’s Federal Theater Project, a government effort to provide work for unemployed theater professionals in the midst of the Great Depression. HUAC concluded the project was dominated by communists and demanded Roosevelt fire the project’s leadership because they had “associates who were Socialists, Communists, and crackpots.” Roosevelt refused to fire the leaders but HUAC convinced the US Congress to cancel funding to the project on June 30, 1939.

In 1945 HUAC became a permanent Congressional committee that launched investigations into “subversive” activities in the US. It undertook an anti-Communist witch hunt in Hollywood in 1947 that placed over 320 actors, directors, and writers on a blacklist forbidding them work. In the same timeframe Joe McCarthy, Senator from the state of Wisconsin, led his own crusade against the hundreds of communists he alleged had infiltrated the US government. The manic anti-Communism that gripped America in that period became known as “McCarthyism” due to the pathological anti-communism of Senator McCarthy and his political allies in official circles.

HUAC repression in Hollywood destroyed careers and purged the entertainment industry of those perceived to be “un-American.” Ten prominent screenwriters and directors who refused to cooperate with HUAC were found in contempt of Congress and each was sentenced to a year in prison; after their release they were blacklisted like all the rest. Government bullying not only purged Hollywood of the left, it ushered in an era of political submissiveness and conformity in U.S. cinema; The Red Menace from Republic Pictures is a perfect example [2].

McCarthyism impacted all facets of cultural life in the US, it was not just the entertainment professionals in Hollywood who suffered; visual artists were also targeted. It is beyond the scope of this article to list all of the painters and printmakers who were persecuted by McCarthyism, but Irving Norman, the painter of social surrealist images comes to mind. US artists would do well to remember the reactionary assault on art during the McCarthy years led by Michigan Republican Congressman, George A. Dondero. On August 16, 1949, Rep. Dondero gave a speech before the US Congress titled, Modern Art Shackled to Communism [3]. He spoke of the “isms” that he said were promoted by communists:

“Cubism aims to destroy by designed disorder. Futurism aims to destroy by the machine myth. Dadaism aims to destroy by ridicule. Expressionism aims to destroy by aping the primitive and insane. Abstractionism aims to destroy by the creation of brainstorms. Surrealism aims to destroy by the denial of reason. All these isms are of foreign origin, and truly should have no place in American art. While not all are media of social or political protest, all are instruments and weapons of destruction.

We are now face to face with the intolerable situation, where public schools, colleges and universities, art and technical schools, invaded by a horde of foreign art manglers, are selling to our young men and women a subversive doctrine of “isms,” Communist-inspired and Communist-connected, which have one common, boasted goal – the destruction that awaits if this Marxist trail is not abandoned.”

Today Congressman Dondero’s words may sound ridiculous, but between the years 1946 and 1956 this was a deadly serious matter. Congress never rebuffed Dondero’s claims; he had very powerful friends and allies. Together they condemned and suppressed modern art exhibits while leading campaigns to censor and destroy “communist” WPA murals located in government buildings. In 1953, acting as the chairman of the House Committee on Public Works during the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower, Dondero was involved in a congressional push to destroy the murals of Anton Refregier that were painted in San Francisco’s Rincon Annex Post Office.

While Congressman Dondero and his supporters were attacking abstract art for being “communist because it is distorted and ugly, because it does not glorify our beautiful country, our cheerful and smiling people, and our material progress,” a few powerful opponents of Dondero both in and out of government were defending abstract art as anti-communist.

The advisory director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Alfred Barr, wrote an essay titled Is Modern Art Communist? for the New York Times in 1952. Barr proclaimed abstract art to be anti-communist and an expression of American freedom and individualism! [4] Here I must remind the reader that Nelson Rockefeller, a major proponent of abstract art, was the president of MoMA in the 1940s and 1950s, and that he initially approved of, but then ordered the destruction of, Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural in 1934.

For twelve years Rivera’s mural would remain hidden behind McAgy’s wall until after Rivera’s untimely death in 1957. That same year McCarthyism and Abstract art began to ebb; the CSFA decided it was safe to take down the wall that hid the fresco mural and rededicate The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City.

As conservative anti-communists and liberal anti-communists fought over how to defeat communism in the arts, as well as how to combat it with the arts, there stood Diego Rivera in the midst of the clamor, painting his mural at the California School of Fine Arts. It is little wonder why Rivera’s fresco was targeted for censorship in 1945. Douglas McAgy’s decision to wall off Rivera’s mural was undoubtedly motivated by the “liberal” anti-communist view, coupled with his being an exponent of abstract art.

What may astonish the reader is that the CSFA, renamed the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) in 1961, makes absolutely no acknowledgment online of CSFA director Douglas McAgy being responsible for building a wall over Rivera’s mural and keeping it covered for a dozen years. Mention of McAgy’s censorship is not even broached on the SFAI website page that supposedly presents the institution’s history.

I have a few rhetorical questions for the students and faculty of the San Francisco Art Institute, as well as for the larger arts community in the U.S. and beyond.

Mexico is in deep crisis, it is in a political, economic, and moral tailspin; since 2007 over 164,000 Mexicans have been killed in the so-called drug war; 10,000 Mexicans have been kidnapped and “disappeared” by death squads since 2012; over 41 Mexican journalists have been assassinated since 2010 for seeking the truth.

I write this on the one year anniversary of the kidnapping and forced disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in Guerrero, Mexico, who were seized by corrupt police officers and their drug gang accomplices. Ayotzinapa has become a dagger in the heart of the Mexican people, and millions of them know who is responsible for conspiring against them.

My questions are – do you really prefer Alejandro Almanza Pereda and his fluorescent light scaffolding over Diego Rivera and his socially conscious mural? Do you actually think Pereda’s is the appropriate artistic response to a Mexico awash in blood and corruption? Do you genuinely believe that art and artists are above the fray, and need not dirty their hands with real world issues? And, faced with all of the inequality and barbarity of this world, do you regard it as apropos to “contend with and complicate the legacy” of these conditions by attacking Rivera?

If you answered “yes” to any of my questions, then I think it safe to say that the arts community is in its own moral tailspin.

— // —

ADDENDUM:

[1] Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University. Howard Singerman. University of California Press. 1999.

[2] The Red Menace – Director, R.G. Springsteen. Republic Pictures 1949. The film offered a fictional account of how the Communist Party USA operated in the city of Los Angeles, using deceit and thuggery to recruit the weak minded. The film is narrated by Lloyd G. Davies, a member of the Los Angeles City Council. One of the film’s communists was played by actress Betty Lou Gerson, who would be the voice actress for Cruella De Vil in Disney’s 1961 animated feature, 101 Dalmatians.

[3] Law, Ethics, and the Visual Arts – John Henry Merryman, Albert Edward, Elsen, Stephen K. Urice. Published by Kluwer Law International, 2007.

[4] The Rise and Fall of American Art, 1940s-1980s: A Geopolitics of Western Art Worlds – Assoc Prof Catherine Dossin. Ashgate Publishing. 2015.