May Day with Diego & Frida

When I first got the news that the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) in Detroit, Michigan would be presenting a special exhibition of works by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, I knew I would be making a trip to the Motor City. My wife and I flew from Los Angeles to arrive at the DIA on May Day, the most appropriate day to visit with my old mentors Rivera and Kahlo.

I had never been to Detroit, let alone the DIA, and found the entire experience eye-opening and inspiring. The DIA is an amazing world class museum with a truly impressive collection. My only regret was that I did not have more time to peruse through every wing of the institution.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit opened at the DIA on March 15th and will run until July 12, 2015. The exhibit features some 70 works from the couple, most of which were done while visiting Detroit from 1932 to 1933 during the Great Depression. The show features 23 paintings, prints, and drawings by Kahlo, with the remaining works having been created by Rivera.

As of this writing I am still working on a review of the exhibit; as a working artist profoundly influenced by the Mexican school of social realism that Rivera and Kahlo were part of, there is so much to cover.

Art critics and reviewers have written positive appraisals of the DIA exhibit, but they have done so with little understanding of Mexican history and the politics embraced by Rivera and Kahlo. As an artist involved with Chicano art and politics in Los Angeles since the late 1960s, I have a better grasp of Rivera and Kahlo.

I view them, not as superstars or interesting figures frozen in a not-so-distant past, but as standard bearers for the type of realist art so desperately needed today. That is especially so for Diego Rivera.

My overall impressions of the exhibit are overwhelmingly positive, and I suggest that everyone who can should make an attempt to see it. However, my praise for the show does not preclude criticism, but you will read all of that in a forthcoming appraisal of the show.

This essay will be the first installment of multiple observations I will make regarding my visit to the DIA; surprisingly enough, this opening assessment does not focus on the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit exhibition, but with my photographs of Rivera’s Detroit Industry fresco murals found in the DIA’s gorgeous Rivera Court.

In 1932 Rivera was commissioned to create the murals by then president of the Ford Motor Company, Edsel Ford. The mural project was encouraged by the DIA’s director at the time, William Valentiner, with the museum providing the wall space for the monumental murals in an interior garden courtyard. Obviously, it was the creation of the murals that brought the couple to Detroit by train in ‘32. Seeing as how Rivera’s monumental sketches for his murals were on display in the special exhibit Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, the murals and the special exhibit can be seen as one organic whole.

My objective in presenting photos of Rivera’s paintings, is to spotlight the craft of his works and to show the artist’s hand in making them. Rather than present a typical photograph that crams as many figures into the shot as possible, I have chosen instead to zero in on extreme, detailed close-ups. My photos give insight into the physicality of Rivera’s frescos, revealing layered washes and underlying charcoal drawings, as well as showing textures and the absorbent nature of the walls Rivera painted upon.

While fresco was practiced in ancient Crete, Greece, and Rome, it is mostly associated with European art of the late Medieval and Renaissance periods. The technique entails painting upon freshly-laid wet plaster with water-based pigments. The plaster absorbs the pigment, and as the two dry they bind, becoming inseparable. It is an unforgiving medium, and with fresco murals as large as the ones painted at the DIA, only so much wet plaster could be trowelled on the walls and painted before the plaster dried, which means that the entire mural cycle had to be painted in small sections.

In 1920 Rivera learned how to create frescos when traveling and studying in Italy, but as an amateur archaeologist well familiar with the ancient fresco paintings of the indigenous Toltec artisans at Tula and the frescos from craftsmen at ancient Teotihuacan, Rivera was inspired to create a new muralism that sprang from Mexico’s own history.

In this, my first illustrated essay on Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals, I am going to set my sights on a certain design aspect of the artist’s frescos, his use of the “predella panel” in buttressing his mural’s overall message.

In European religious altarpiece paintings from the late medieval and Renaissance period, a central figure or depiction would be augmented by a series of small panel paintings, the predella, images that added to or reinforced the overall narrative.

Rivera’s predella panels were painted like traditional grisaille paintings. As a technique, grisaille (pronounced greeze-eye) goes back as far as the late Middle Ages, but it continues to be used today; I use the technique on some of my own oil paintings. Basically it means to paint monochromatically in shades of grey (sometimes in burnt umber), the name for the method coming from “gris,” the French word for grey.

Grisaille can be a monochromatic painting completed in one color, or treated as an underpainting painted over with glazes of color, the technique I choose. Rivera’s grisaille predella panels give the illusion of sculptural friezes.

In painting his grisaille predella panels, Rivera was no doubt also thinking of the Mexican folk art art known as “retablos,” small devotional paintings of Saints or other religious figures that are created on tin, copper, or wood. Many people in the Southwest of the U.S., especially those of Mexican heritage, are familiar with retablos… I have a few in my own house.

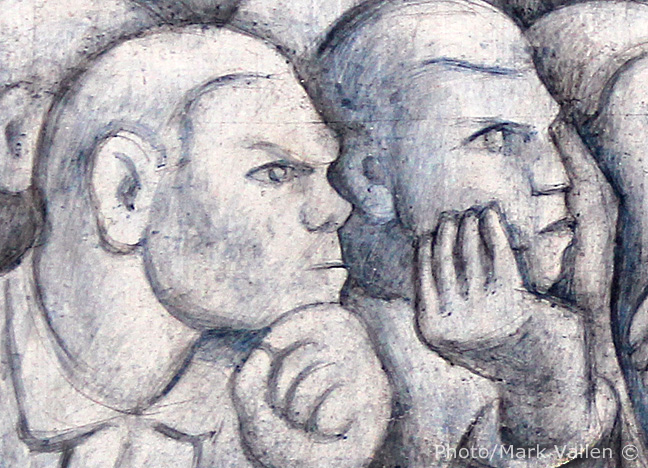

But Rivera was not thinking of Catholic saints when he painted Detroit Industry, we was extolling the working class. Rivera’s predella panels were painted monochromatically in tones of blue and grey, each surrounded by a fresco tromp l’oeil frame of bolted green steel. Each predella depicted the workers daily life at an auto plant and the labor associated with automobile manufacturing.

To wrap up this intro, the DIA allows photography of the Detroit Industry murals in Rivera Court, provided you do not use a tripod. I used my Canon Rebel T2i camera with a 17-55mm zoom lens for paintings at eye-level, and a 70-300mm telephoto lens for extreme close-ups and shots of figures placed high up in the mural. Considering the ceiling at the Rivera Court consists of a magnificent laminated glass skylight, I used nothing but natural light for my photos. All quotes by Rivera that appear in my essay come from his personal history, Diego Rivera – My Art, My Life: An Autobiography.

In 1932 the workers at Ford labored under deplorable conditions. They had no union to protect their rights, and Ford liked it that way. What makes this painting so poignant is that at the time workers were forced to work one long grueling shift with only a brief respite for lunch. They would not win the right to two fifteen-minute rest periods per shift, amongst other basic rights, until 1941.

Rivera’s works were actually based upon his observations of workers at Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge Plant. As the artist noted:

“I studied industrial scenes by night as well as by day, making literally thousands of sketches of towering blast furnaces, serpentine conveyor belts, impressive scientific laboratories, busy assembling rooms; also of precision instruments, some of them massive yet delicate; and of the men who worked them all. I walked for miles through the immense workshops of the Ford, Chrysler, Edison, Michigan Alkali, and Parke-Davis plants. I was afire with enthusiasm.”

Rivera said that Edsel Ford placed only one condition on the creation of the murals, “that in representing the industry of Detroit, I should not limit myself to steel and automobiles but take in chemicals and pharmaceuticals, which were also important in the economy of the city. He wanted to have a full tableau of the industrial life of Detroit.” Close examination of the Detroit Industry mural cycle reveals that Rivera also depicted workers involved with the pharmaceutical, chemical, transport, weapons, steel, and medical industries, all of which were dynamic in Detroit at the time.

When Rivera and Kahlo arrived in Detroit the Great Depression was strangling the city as well as the rest of the country. Thousand of workers at Detroit’s great auto plants had been laid-off and those that remained had their wages severely cut. Auto workers labored long hours for an annual salary of $757. The workers had no union and enjoyed no company benefits. There was no such thing as unemployment insurance or social security. The banks had collapsed and workers became impoverished. Detroit workers suffered joblessness, poverty, homelessness, and utter despair.

Eventually the workers decided to march on the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge Plant on March 7, 1932 in what they called The Ford Hunger March. The workers rallied behind a set of demands; jobs for all laid off Ford workers, the right to organize a union, a seven-hour work day without a reduction in pay, free health care for all Ford workers whether employed and unemployed, no discrimination against blacks and an end to racist hiring practices, no speed-ups, two fifteen-minute rest periods per shift, no foreclosures on the homes of Ford workers, and the abolishment of company spies and armed thugs.

All of the demands from The Ford Hunger March were equally important, but I have to elaborate on the demand regarding the use of armed thugs at the Ford River Rouge Plant. Henry Ford was fiercely anti-union, he hired the notorious Pinkerton Detective Agency, known for its brutality, to physically keep the workforce in line and free of union organizers.

Ford also organized an internal “Service Department,” a private security army of armed thugs that was used to defeat the workers’ union movement. Ford appointed a pugnacious ex-navy boxer named Harry Bennett to lead the force of over 8,000 men that used blackjacks, brass knuckles, clubs, whips, and guns to intimidate the workers in every Ford plant; Bennett quickly became Ford’s most trusted underling. Quoting the Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History by Eric Arnesen, in the 1930s the Ford Service Department was “the world’s largest private army, whose purpose was to disrupt union organizing efforts using espionage, physical intimidation, and violence.”

Through Ford’s connections, Harry Bennett was appointed to the Michigan Parole Board. Arnesen wrote that Bennett used that position to have “men who had been convicted of violent crimes released so they could enter his service.”

Service Department thugs regularly attacked union organizers attempting to distribute flyers to the workforce.

Arnesen wrote that the United Auto Workers, then struggling to be recognized by the Ford Motor Company, “compared Ford’s repressive methods to those of European fascism, and branded the Service Department, ‘Ford’s Gestapo.’”

Some of the men recruited into the Ford Service Department were likely from the terror organization, The Black Legion, a group I wrote about extensively in my January 2013 article, Maurice Merlin & the Black Legion. Based in Michigan, the Black Legion was a white supremacist gang that targeted African Americans, Jews, union organizers, and leftists.

Auto worker union activists were convinced that members of the shadowy Black Legion were employed by the Ford Service Department, the goons of which were to play a loathsome role in attempts to squelch the labor movement.

Braving bitter cold and snow some 5,000 workers and their families participated in The Ford Hunger March. They carried banners that read, “Give Us Work,” “We Want Bread Not Crumbs!” “Don’t starve to death in the richest land on earth,” “Negro, White, Unite!” “Fight Evictions!” and “Tax the Rich and Feed the Poor.” When the workers finally made it to the Rouge Plant, they were attacked by the Police and the Ford Service Department, who together fired volleys of live ammo at the unarmed protesters, even using machine guns.

Four workers were killed and fifty more were injured. What had been organized as The Ford Hunger March, turned out to be The Ford Massacre.

In the massacre’s aftermath the repression continued; hundreds of workers were fired at Ford plants for having union or leftwing literature, those who were hospitalized from violence at the Hunger March were arrested in their hospital beds, some even handcuffed to their beds. Labor organizations and offices of the Communist Party were raided and their members arrested. The Detroit Free Press reported that professional communists were responsible for “the assaults and killings which took place before the Ford plant.” Yet the workers and the burgeoning labor movement held strong. On March 12, 1932, over 80,000 workers held a funeral procession for the four slain workers, who were buried at the Woodmere Cemetery.

A month after the March 12th procession for the martyred workers, Curtis Williams, a committed African American auto worker activist who suffered a vicious police clubbing and inhalation of tear gas at the Ford Massacre, died of his wounds at Ypsilanti State Hospital. The Woodmere Cemetery refused to bury him because he was black. The Communist Party U.S.A. released a statement that in part read:

“At the direct orders of Ford, with the understanding and consent of Mayor Murphy and his police department, the board of directors of the Woodmere Cemetery uncovered their hidden policy of segregation, Jim Crowism, and race discrimination and white chauvinism, by bluntly refusing to permit us to bury the body of Curtis Williams beside that of the rest of our dead. Comrades Joe York, Joe Bussell, Joe DiBlassio, and Coleman Leny, the first victims of the bloody Ford Massacre. This is another attempt by the boss class to split the growing unity of Negro and white workers.”

Mass protests and complaints eventually forced the Woodmere Cemetery to compromise. Williams was admitted to the the cemetery for cremation, but the facility would still not allow a burial. The workers’ movement responded by hiring a plane and scattering the remains of Williams over the cemetery and the Ford River Rouge Plant.

This rare silent footage titled Ford Massacre, is the only known film of The Ford Hunger March, the company/state violence that stopped it, and the resulting militant workers funeral march for the slain. It was produced by the Detroit and New York branches of the Film and Photo League, a national collective of filmmakers, photographers, projectionists, writers, and artists dedicated to using film and the photographic arts to bring about radical change. While a good number of the members were Marxists, the league supposedly operated “independently” from the Stalinist Communist Party U.S.A.

The despair of the Great Depression and the terror of the Ford Massacre describes the political atmosphere of Detroit when Rivera and Kahlo arrived. One cannot truly understand or appreciate the Detroit Industry murals without knowing this history.

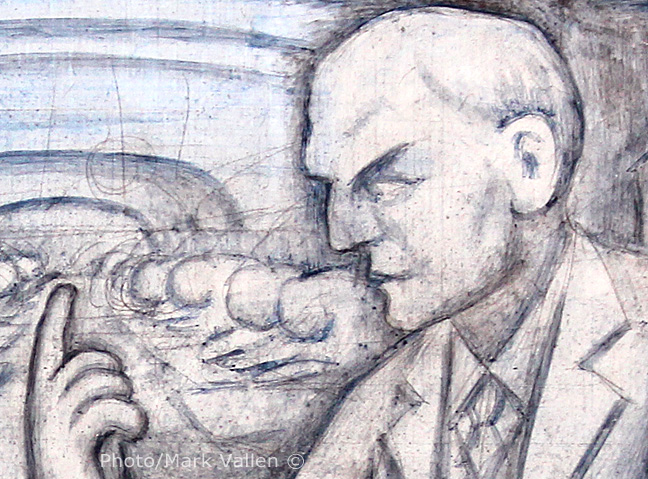

I think the predella panel that shows Henry Ford giving a lecture to the workers is the most interesting panel in the series; it certainly illustrates Rivera’s sense of humor. Knowing that Rivera reviled capitalism, the panel is also a swipe at Henry Ford. The painting has religious overtones and contains a veiled critique of capitalism as a theology.

The tableau of the godlike Henry Ford, his finger pointed to the heavens as he lectures the workers, is somewhat evocative of The Creation of Adam, the most well-known panel from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel mural series – which was also done as a fresco. But instead of being surrounded by angels as in Michelangelo’s depiction of the Lord, Henry Ford stands before a backdrop of slavish laborers too hard-pressed to look up from their drudgery for even a moment.

The reference to religion in this image continues to strike me. In Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, the apostle Thomas was painted with his finger pointing to heaven, likewise, Leonardo painted St. John the baptist in the same manner.

In 1921 the German Marxist philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote an unfinished essay titled, Capitalism as Religion. If Rivera had not read Benjamin’s tract, he certainly understood the concept as presented by a fellow Marxist. Benjamin wrote:

“One can behold in capitalism a religion, that is to say, capitalism essentially serves to satisfy the same worries, anguish, and disquiet formerly answered by so-called religion.” Benjamin went on to write, “First, capitalism is a pure religious cult, perhaps the most extreme there ever was. Within it everything only has meaning in relation to the cult: it has no special dogma, no theology. From this standpoint, utilitarianism gains its religious coloring.”

As far as Benjamin saying “capitalism is a pure religious cult,” he could have said the same of communism—but he didn’t mind serving as clergy in that organized religion. Being a Jewish Marxist, Benjamin fled Germany for Paris in 1933 when the Nazis took power, the same year Rivera finished his Detroit Industry murals. Benjamin beat a hasty retreat from Paris when the Nazis seized it in 1940, he eventually wound up on the French-Spanish border that same year where he committed suicide at the age of 48 to avoid capture by the invading armed forces of Nazi Germany.

Unlike Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam Sistine Chapel painting, Ford is not face to face with Adam, a creation made of dust into which the Lord blew “the breath of life.” Rivera painted Ford standing before a group of workers, who by the looks on their faces have sized up their boss and concluded that they could run the factory just as well without him.

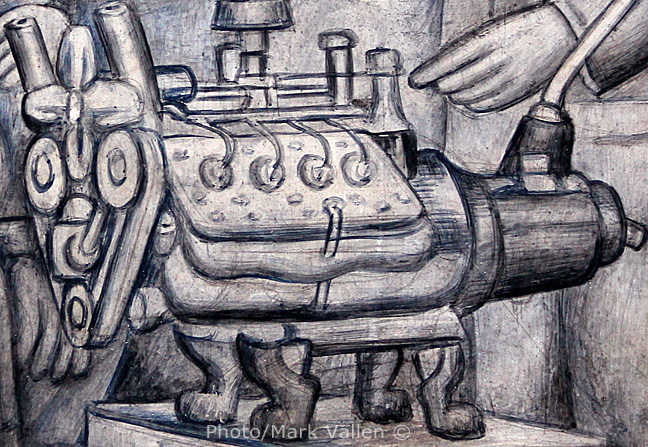

Some have noticed that the V8 engine near Ford resembles a pre-Conquest sculpture of a small, hairless Mexican dog. It is commonly known that the indigenous people of Mexico used the diminutive dogs as a food source, but the spiritual and ritualistic symbology of the dog is not so well known outside of Mexico. As an amateur archaeologist and avid collector of pre-Conquest indigenous art, Rivera knew a thing or two about these dogs.

In ancient Mexico it was thought that a dog accompanied a person’s soul to the underworld. On the famous Mexica-Aztec calendar stone there is a glyph of a dog named Itzcuintli (Eeetz-kween-tlee). He was one of 20 day-sign glyphs that surrounded the depiction of the sun god appearing at the center of the stone. Itzcuintli represented a period of 13 days ruled by Xipe Totec (Our Lord of the Flayed Skin), deity of spring and agricultural renewal.

The Mexica-Aztec people used the hairless dogs in prayer rituals to Tlaloc, Lord of rain and water. The dogs were sacrificed to Tlaloc, one of the most important Aztec deities, and their bodies were then eaten in ritual feasts. Rivera gave a zoomorphic treatment to the V8 by turning the engine into a dog, but he also gave that dog the iconic face of Tlaloc.

In late 1933, as Rivera was finishing up work on his murals, a group of some 200 workers marched into the center of the courtyard, the leader shouting “We want Diego Rivera to come here!” The artist descended from his scaffold and walked up to the burly worker who had called for him. One of Rivera’s painting assistants, Cliff Wight, served as translator, delivering the extraordinary message from the American workers to the Mexican artist. Rivera described what the lead worker told him:

“Waiving all ordinary social preliminaries, he acknowledged my presence with a nod of his head. ‘We are Detroit workers from different factories and belonging to different political parties. Some of us are Communists, some are Trotskyites, others are plain Democrats and Republicans, and still others belong to no party at all.

You’re said to be a man of the left opposition, though not a Trotskyite. In any case, you’re reported to have said that, as long as the working class does not hold power, a proletarian art is impossible. You have further qualified this by saying that a proletarian art is feasible only so long as the class in power imposes such an art upon the general population. So you have implied that only in a revolutionary society can a true revolutionary art exist. All right! But can you show me, in all these paintings of yours, a square inch of surface which does not contain a proletarian character, subject, or feeling?

If you can do this, I will immediately join the left opposition myself. If you cannot, you must admit before all these men, that here stands a classic example of proletarian art created exclusively by you for the pleasure of the workers of this city.’”

Rivera was overwhelmed, and agreed with the workers assessment of his mural. He would write later that he “was deeply touched by this tribute from a representative of the working class of the industrial city I wanted so much to impress.” The group of workers also informed the artist that they were well aware of “much talk against your frescoes, and there have been rumors that hoodlums may come here to destroy them. We have therefore organized a guard to protect your work. Eight thousand men have already volunteered.”

The following Sunday Rivera had completed his fresco murals, and they were put on view for the general public to see for the very first time. As promised, the auto worker’s volunteer guardians were there in force. They checked each person that entered the DIA, having each sign their name and address in a registration book. In order to accommodate the massive crowds on that premiere day, the DIA stayed open until half past one on Monday morning. When the museum finally closed its doors on the first day of the exhibit… there were eighty-six thousand signatures in the registration book.

In 1941 the workers movement finally won union recognition and forced the Ford Motor Company to enter a collective bargaining agreement with the United Automobile Workers (UAW).