Salvador Dalí – Avida Dollars

Starting February 16th and running until May 30th 2005, the Philadelphia Museum of Art will present Salvador Dalí, a broad retrospective of the artist’s works -the first in the United States in over 60 years. Co-curator of the exhibit, Michael Taylor, said “It’s astonishing, the range of his work. It’s really crucial, I think, to the re-evaluation of his career.” As the media, historians, and art critics have another look at Dalí, it is indeed time for a new examination of the artist’s life.

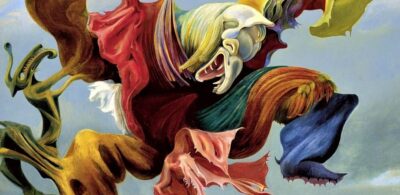

As a nine year old in 1963, I cracked open an art book presenting the works of Salvador Dalí, and became transfixed by his 1936 painting, Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of the Spanish Civil War). The bizarre painting of a grotesque monster pulling itself apart refused to convey any meaning to me whatsoever, yet I was spellbound by the image. It was one of those formative moments in life when I knew providence would make me an artist. As I matured so too did my fondness for the Surrealist painter, and by sixteen I had developed a full blown obsession with Dalí’s works. A few years later, as I turned to reading history, I discovered that Soft Construction with Boiled Beans was not a premonition, and that my idol was not the founder of Surrealism.

I was surprised to learn about the original 1924 Parisian Surrealist group (to which Dalí was admitted in 1929). Founded and led by the French writer André Breton, the group included members like Max Ernst, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy. The Surrealists had as their goal the total revolutionary transformation of society. They believed the subconscious was the wellspring of a liberated art, and they refused any restraints, whether brought to bear by reason, aesthetics, or morality. Dalí was influenced by Surrealism in 1924 after exposure to La Révolution Surréaliste, the journal edited by André Breton.

Dalí put aside his early cubist approach and took up the banner of Surrealism. He collaborated with friend Luis Buñuel in creating the film, Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). The Surrealist movie premiered in Paris 1929 and received a standing ovation from an audience composed of Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Fernand Leger, Tristan Tzara, and the entire Surrealist entourage. Soon after Dalí and Buñuel were inducted into the Surrealist circle, and Dalí’s early years in the group were rewarding. But by the late 30’s his creeping ultra-conservatism caused him to fall out of favor with his fellow artists, and he was ultimately expelled as a renegade in 1939. When referring to André Breton’s eventual criticism of Dalí, the Philadelphia Museum’s promotional material makes it sound like a case of mere professional jealousy.

“Breton had long thought Dalí’s art had become too commercialized and that Dalí’s growing fame threatened the unity and agenda of the Surrealists. His growing disgust with Dalí’s financial success as an artist led him to dub Salvador Dalí with the anagrammatic nickname ‘Avida Dollars,’ describing what he perceived as Dalí’s greed for money and fame. Though no longer associated with the Surrealists, Dalí never abandoned his Surrealist pursuits entirely.”

André Breton’s disapproval of Dali had nothing to do with the Spanish painter’s “financial success”, rather, it was an issue of political integrity. Breton had an excellent relationship with the Mexican Muralist, Diego Rivera, who enjoyed financial success and the largesse of wealthy patrons while continuing to develop a revolutionary art.

Dalí on the other hand immigrated to the US to sit out the war years and pursue a capitalist-style career. He lived in America from 1939 to 1948, where he became a master of exhibitionism and self-promotion. He was the darling of advertisers, who used him to sell every imaginable product. He worked for Disney and created a cinematic sequence for Alfred Hitchock’s, Spellbound. His meticulously cultivated flamboyant persona and thoroughly orchestrated eccentricity guaranteed a public perception of him as the ultimate Surrealist artist – it also brought him a personal fortune estimated at over $30 million dollars. Breton was not off the mark in bestowing upon Dalí the anagram of Avida Dollars (meaning Greedy for Dollars), in fact Dalí was so venal when it came to wealth that he enthusiastically embraced the anagram as a nickname.

But Surrealist ire towards Dalí had less to do with his greed, and far more to do with his dubious political opinions. War and fascism were on Europe’s horizon, and the Surrealists moved further to the left when the Nazis seized absolute power in 1933 and Germany began its decent into barbarism. Hitler initiated an unprecedented campaign of terror – civil rights were no more, artists and intellectuals began to flee the country, book burnings had begun, more than 25,000 Communists, Socialists, and Jews had been sent to concentration camps – and that was just the beginning. Tensions developed within the Surrealist group as Dalí evaded anti-fascist political ideas and actions and instead showed an obsessive interest in what he called the “Hitler phenomenon.”

As Dalí’s infatuation with Hitler grew, he came under suspicion by his fellow Surrealists. In 1933, instead of condemning Hitler, Dalí painted and exhibited The Enigma of William Tell, a semi-nude portrait of Lenin with a huge anamorphic buttock. The Surrealists saw the painting as a provocation – especially since the Nazis were busy murdering people for being communists.

Dalí defended himself by saying, “No dialectical progress will be possible if one adopts the reprehensible attitude of rejecting and fighting against Hitlerism without trying to understand it as fully as possible.” Surrealist misgivings concerning Dalí’s political loyalties led him to sign a declaration that he “was not an enemy of the proletariat,” but the situation only worsened with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. In 1936 General Franco’s Nazi-supported troops led a revolt against the democratically elected government seated in Madrid.

While the Surrealists and artists worldwide reacted to the outrages of fascism against the Spanish Republic, Dalí painted his, Soft Construction with Boiled Beans, a work that many art critics have mistakenly construed as being “antiwar.” Commenting on the canvas, the Philadelphia Museum’s promotional material states;

“Though Dalí intended this painting as a comment on the horrors of the Spanish Civil War, he did not openly side with the Republic or with the fascist regime. In fact, the painting is one of only a few works by Dalí to deal with contemporary social or political issues. Unlike other Spanish modernists, including Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró, who used their art to make political statements in support of the Spanish Republic, Dalí preferred to remain apolitical.”

The co-curator of the Philadelphia Museum exhibit, Michael Taylor, said that Dalí “wants the Spanish Civil War to be seen as a really monstrous thing that’s ripping the country apart. He didn’t want to take sides. I think Picasso wanted to take sides.” Thank goodness Pablo Picasso took sides! The Condor Legion was a unit of the Nazi air force or Luftwaffe, created by Hitler to assist Franco.

On April 26, 1937, German Condor Legion bombers attacked the ancient Basque village of Guernica, killing nearly 2,000 people in history’s first arial mass bombing of a civilian population. Picasso’s response was to paint a masterwork, Guernica, perhaps the 20th century’s greatest antiwar painting. How could one not have taken sides when Mussolini’s tanks and Hitler’s air force assisted Franco’s troops in extinguishing democracy in Spain?

It is a fallacy to think Dalí “remained apolitical” while Spain was cut to ribbons by fascist bayonets. Silence sometimes masks complicity, but Dalí pledged his full and unwavering support for the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

That pledge to Franco resulted in Dalí being thrown out of the Surrealist movement for good, but his 1939 painting The Enigma of Hitler (which now hangs in the Museo Nacional Reina Sofia, Madrid) also contributed to his expulsion. Dalí had inserted a small portrait of Adolph Hitler in the barren surreal landscape. The prior year had seen the whirlwind of anti-Semitic hatred known as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) explode in Germany.

Hundreds of Jewish synagogues were torched, thousands of Jewish businesses were looted, and 30,000 Jews were sent to the concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen. Against that appalling backdrop Dali dared to portray Hitler as an “enigma.” The Surrealists could no longer put up with Dali’s conduct and decided to expel what they considered a reactionary impostor from their ranks.

Eventually Dalí returned to Franco’s Spain after the war, and it no doubt endlessly pleased the dictator to have the celebrated artist living and working there when few other well known personalities would. Dalí announced his conversion to traditional Catholicism, and the sacred art he created in the 1950’s became some of his most popular works worldwide. Long gone was Dalí the rebel anticleric, the scatological genius, the anarchistic surrealist. But even his religious paintings, surreal Madonnas and crucifixion scenes, seemed tainted inasmuch as they were the type of artworks fully sanctioned by the fascists who lorded over Spain.

After having overthrown the duly elected government, General Franco ran Spain with an iron fist until his death in 1975. The country’s first democratic elections since 1936 were held two years after Franco’s demise. SalvadorDalí passed away in 1989, at the age of 85.

I write these words not as a detractor of Dalí’s works, but as someone opposed to the revisionism surrounding his history. To be honest, I still admire Dalí as an accomplished painter, and I find genius in the works he produced throughout his long career. But one must be honest about Dalí’s considerable flaws in order to properly re-evaluate his contributions to art. The Philadelphia Museum does a disservice to its patrons and to history by asserting “Dalí never abandoned his Surrealist pursuits entirely.”

Surrealism was always much more than a decorative fantasy art composed of bizarre landscapes filled with melting watches. It was a complete philosophical, political, and aesthetic program that by the late 1930’s had been entirely discarded by Dalí.

The year 2004 was celebrated as the 100th anniversary of Salvador Dalí’s birth. The chairman of Spain’s Dali Year Commission stated in 2004 that if Pablo Picasso (who was a communist), received “international acclaim, then Dalí, who admittedly supported fascism in Spain, should receive his own homage.” In light of such a statement, it is astonishing that the Philadelphia Museum of Art can still say that Dalí “preferred to remain apolitical”.

A version of this article with several beautiful illustrations, historic photos, and multiple informative links, is available at: www.art-for-a-change.com/content/essays/dali.htm