Lost Horizons: Edward Biberman

In August of 2014 the Social And Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) in Venice, California, presented a small but important exhibition titled Lost Horizons: Mural Dreams of Edward Biberman. The American realist painter Edward Biberman carved out a place for himself in mid-20th century Los Angeles, despite the ascendancy and domination of abstract expressionism. His figurative paintings examined social inequality, racial oppression, and the plight of workers, placing him in the school of Social Realism. But his paintings focusing on the architecture of Los Angeles and the new—at the time, freeways of L.A., exposed his modernist side.

I encourage one and all to read my February 2009 article, Edward Biberman Revisited, an appraisal of a retrospective exhibit of the artist’s works that was shown at the L.A. Municipal Art Gallery at Barnsdall Park. My review included biographical details about Biberman, as well as providing a social context to his works by taking into account the times and events he lived through. In May of 2012 I followed up with a second article titled Biberman Redux, which focused on the artist’s illustrated biographical book, Time and Circumstances: Forty Years of Painting.

In this evaluation of SPARC’s Lost Horizon show, I offer a few observations about some of the works that were exhibited, but mostly I will allow Biberman to speak for himself by inserting those quotes by the artist that SPARC used as plaques in the exhibition.

Lost Horizon takes as its theme the studies for “unrealized” murals that Biberman planned for L.A., but for one reason or another never got the chance to create. The show presents more than a dozen vibrant preliminary sketches and small oils related to proposed murals, as well as a few large paintings that were completed as stand alone easel paintings, such as an oil painting of the African-American artist and communist activist, Paul Robeson. Let’s not forget that Robeson won the Stalin Peace Prize in 1952, and that he praised Joseph Stalin for his “deep humanity.”

It should be noted that Biberman leaned to the hard-left, and there’s little doubt he was more than sympathetic to the Communist Party USA. In the late 1930s he attended meetings of the L.A. based Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL), which warned of the rising threat of fascism in Europe. Biberman’s association with the HANL brought him to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), who identified the HANL as a communist front organization. In 1947 HUAC convened in Los Angeles and began investigating communist subversion in the motion picture industry. In October 1947 Edward’s brother, screenwriter and director Herbert Biberman, was called before HUAC. When he refused to cooperate with the committee, he was found guilty of “contempt of Congress,” fined $1,000, and sentenced to six months in a federal prison. Herbert was later blacklisted by the Hollywood studios and banned from Hollywood until 1965. The brothers Biberman never fully recovered from the HUAC investigations.

On display at Lost Horizon was a work charged with historic meaning, Biberman’s 1940 mixed media drawing titled Chains. An unusual depiction of racial harmony for its time, the art depicts blacks and whites standing shoulder to shoulder in solidarity, defiantly holding hands as if determined not to let someone pass through their lines. Technically, the drawing was produced on a board painted with white gesso. Once that ground was completely dry, Biberman blocked in fields of color, then completed the work with a drawing in black chalk. Throughout the artwork the brushstrokes set in the gesso add amazing textures to the paint washes and chalk drawing.

One must understand how completely segregated U.S. society was when Biberman created Chains. A year after he made the artwork, mass rallies by blacks protesting racial discrimination in the defense industry resulted in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 8802, which desegregated war production factories and banned discrimination in defense plants. In 1948 the U.S. armed forces would be fully desegregated by Executive Order 9981 made by President Harry Truman – eight years after the creation of Chains.

The crucial beginnings of the mass Civil Rights Movement were still a decade away, making Biberman’s artwork look prescient. Chains was an appeal to blacks and whites for unity in the face of virulent racism; given the state of race relations in the U.S. at the time, the artwork was explosively controversial.

Biberman’s sketch, The Civil War and the Role of the Black Soldier: Full Scale Battle, was one of several preparatory studies for murals that the artist never actually painted. On the whole, the dynamically composed drawings depicted circumstances through the eyes of African-Americans. Here I present a mere detail of Full Scale Battle, just to show the technical virtuosity of Biberman. The sketch was first laid out using a pencil to establish a line drawing, broad areas of color were then defined with pastel chalk, and final touches indicating highlights were then daubed in oil paint. A chaotic battlefield comes to life in Biberman’s study; one can almost hear the shrieks of wounded men and the thunder of rifles and cannonade. But the visuals of armed blacks fighting for their liberation was no doubt unsettling for mainstream America in the late 1930s, and Biberman’s vision was never realized as a public mural. Lost Horizons was worth attending if only to view these particular mural studies.

The last series of studies shown at SPARC that I will mention here are from Biberman’s proposed 1938 mural, History of Writing. He planned to install the mural at the San Pedro Post Office located in San Pedro, California, a major international seaport and city with a rich history of radical labor organizing. The mural was beautifully composed and meant to hang on an interior wall of the post office between the lobby and the main workroom. As the title implied, the mural presented important moments in the development of written language.

Rather than have his mural start with the cuneiform of ancient Mesopotamia, Biberman boldly focused on the “talking knots” or “Quipus” of the ancient Inca. “Quipus” were knotted cords that recorded data using binary code similar to modern computer language. Anthropologists have concluded that the Inca used the talking knots to record numerical information regarding time, taxes, census records, and the like, but only recently have anthropologists started to consider the talking knots as an actual writing system.

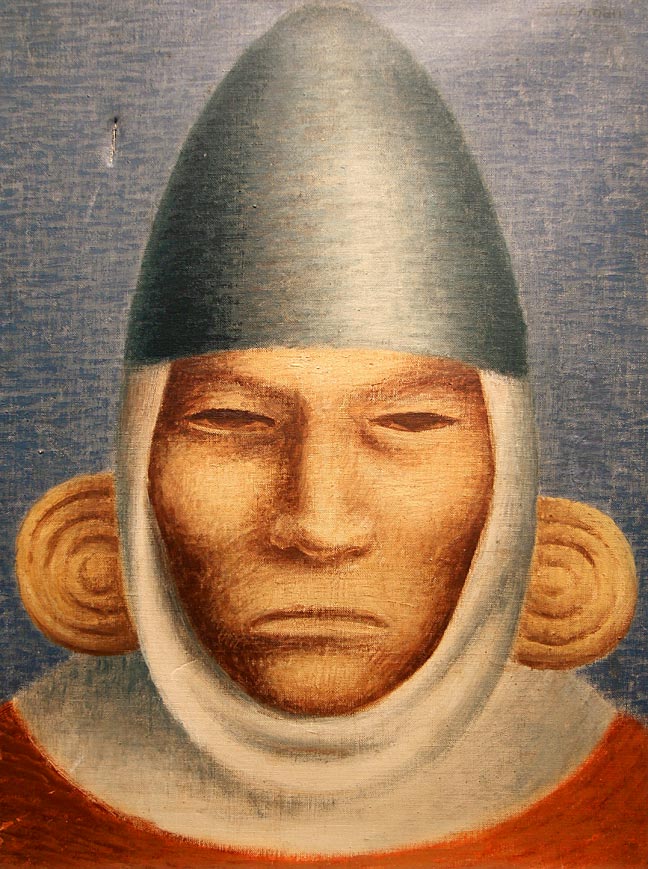

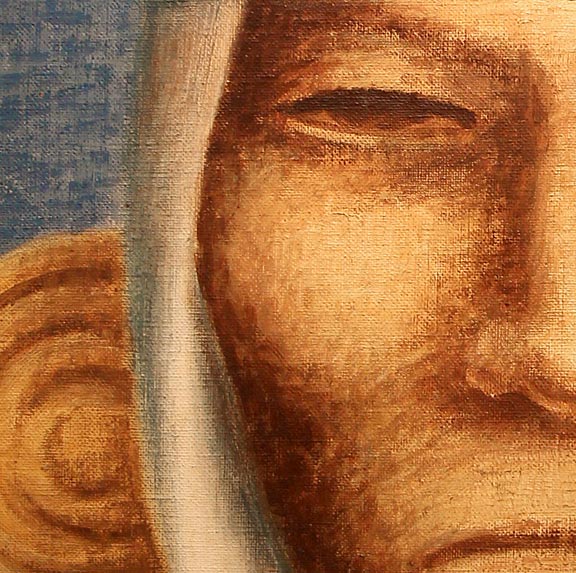

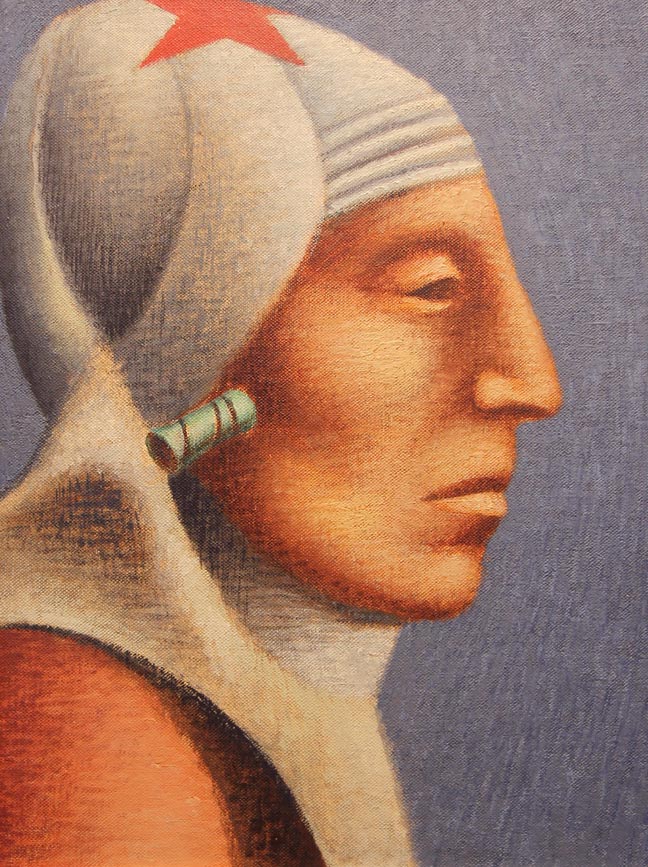

On the left side of his composition study for History of Writing (the original full study for the mural was on display at SPARC), Biberman depicted a number of Inca elites grouped together. The artist created small oil on canvas portrait studies for each figure, two of which appear here as illustrations. I believe that in part, it was his exposure to the Mexican Muralist school that led Biberman to feature the Inca in his History of Writing mural; he had already met Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco while living in New York.

In 1934 Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads fresco mural in New York’s Rockefeller Center was ordered destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Why? Because Rivera had refused to remove from his composition a portrait of the Russian communist revolutionary, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. That same year, American artists inspired by Rivera painted murals in San Francisco’s Coit Tower; some objected to the pro-worker murals and demanded their destruction. Public support prevented the obliteration of the artworks, but the city Park Commission did censor one of the mural panels by artist Clifford Wight, who had included the hammer and sickle symbol of communism in his composition – the symbol was painted out by the authorities.

I cannot help but think that Biberman was thinking of all this when he created preliminary sketches and paintings for his 1938 History of Writing mural. In his oil painting study of an Inca chieftain , he portrayed the leader wearing heavy gemstone earplugs and a cap decorated with a red star – the cap bore more than a little resemblance to the early Soviet Red Army “Budenovka” cap. While visiting Los Angeles in 1932, Siqueiros painted the mural, Retrato del Mexico de hoy (“Portrait of Mexico Today”); the mural included a Soviet Red Army soldier wearing a Budenovka cap.

I am closing this article with some statements made by Edward Biberman, quotes that appeared as wall plaques in the Lost Horizon exhibit. The source of the quotations were a series of interviews conducted in 1975 under the auspices of the Oral History Program of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Biberman’s ideas about art are every bit as relevant to our present circumstances as they were in decades past, and contemporary artists have much to learn from him.

Here is what Biberman said about Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco…

“I had enormous admiration, particularly in this period, for the motivation that drove these artists (Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros) to do the work they did. And although I had no sense of how this might happen in our own country – because this was prior to the whole New Deal art period – I had a feeling that something had to give, that the premise upon which we had all been operating in the past was no longer valid.

Well, the business of being an easel painter and producing what the economists call a ‘commodity’ in the hope that somewhere, sometime, someone would buy it, this is what I mean by the premise. The premise of public art is totally different. You don’t paint an enormous wall in the hope that someday, someone will build a building for it. In public art, you have a building, you have a premise, you have an opportunity, and the opportunity and the audience are both public. Therefore, it seemed to me at the time, and I still feel it is true, that given a different premise, one arrives at a different conclusion in art, as well as logic.”

Biberman said the following about the Great Depression and social realist art…

“But this became a time of deep personal tragedy. This was the bottom of the depression years, and the entire country seemed mired in despair. In the early summer of 1933, my father, despondent over financial worries and seeing no light ahead, took his own life.

The tragic act brought into sharp focus a state of unease, which has been growing in me for several years. Though I had been very fortunate, as a young painter, in getting my work seen, I was sorely troubled by such acts of desperation as that which had now struck our family, and I saw this as but a part of the larger travail of a nation with seventeen million unemployed. I questioned the relevance of my own work, and that of my colleagues, in times such as this. By contrast I had met Diego Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros at various times in New York in these years, and I could not but feel that what they were painting, and the uses to which their work was being put, had a pertinence which I deeply envied.”

On abstract art…

“I always find it not without a kind of coincidental interest that the height of the abstract expressionist movement was also the height of the McCarthy period. This may be, again, speculative, but I have always found the point of view of nonobjective art to be a very limited one. Action painting, abstract expressionism, and the avoidance of associate values in painting have, for me, not been constructive, despite the fact that historically this has been considered to be the emancipation of American art. Most people who write about the art of the middle of the twentieth century speak about the fact that the center of art and the center of the experimental movement moved from Europe to the United States, and that the so-called New York School (which means the abstract expressionist and the action school), signaled the emancipation of American art, and that for the first time American art moved to the center of the world scene.

From my point of view, if this is the center of the world scene of art, it’s not a very good center. I don’t enjoy it, I don’t feel comfortable with it, and I don’t feel it’s a very contributive point of view. My speculation as to why this particular point of view, which avoids subject matter, coincided almost exactly with the Cold War is something which one cannot prove. The painters of the abstract expressionist and action schools did not have to wrestle directly with contemporary social issues. A great many artists and critics maintain that this is a very positive outgoing manifestation of the individualist, a democratic, forward-looking point of view in art. I do not subscribe to this thesis.”

Biberman’s suspicions as to why abstract art became dominant during the Cold War were borne out in research done by British journalist and historian Frances Stonor Saunders and published in her 1999 book, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. Using declassified U.S. government records, Saunders documented how the CIA – from the late 1940s until the late 1960s – ran secret operations that promoted American Abstract Expressionism and modern art as a weapon in the Cold War. From covertly funding museums and galleries that showed abstract art, planting positive stories about abstract artists in newspapers and magazines, and secretly organizing traveling national and international exhibitions of abstract art, the CIA helped to shape abstract art and its successes.

One can only imagine how Biberman would have reacted to Saunders’ findings. While Biberman could only speculate on the existence of a secret U.S. government program that exerted control over the arts, Saunders has provided clear and verifiable evidence of the extensive covert operation, vindicating Biberman’s suspicions. It is instructive that today’s art critics and art press have not yet initiated a discussion regarding the facts brought to light by Saunders.