Ayotzinapa; Between pain and hope

El Día de la Revolución is celebrated every year in Mexico on the 20th of November. The occasion this year marks the 104th anniversary of the 1910 revolution that overthrew the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. This year however will be different. The government has cancelled the annual military parade that ordinarily fills the capital’s streets. Instead, the Mexican people will participate in a nationwide protest and a general strike on Nov. 20, 2014. They will continue the protests against the government kidnapping and probable murder of 43 students that has outraged Mexico for almost two months.

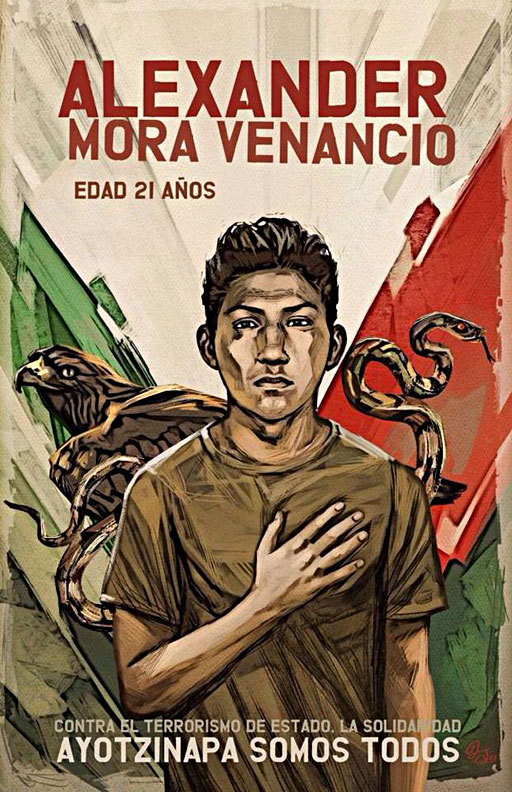

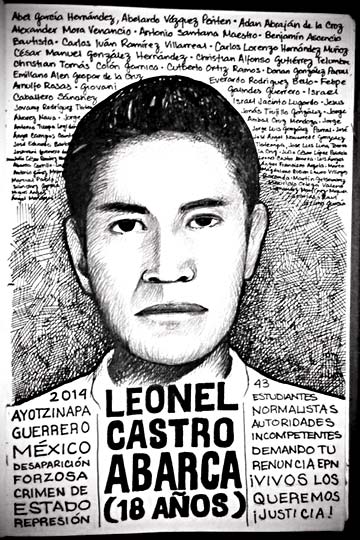

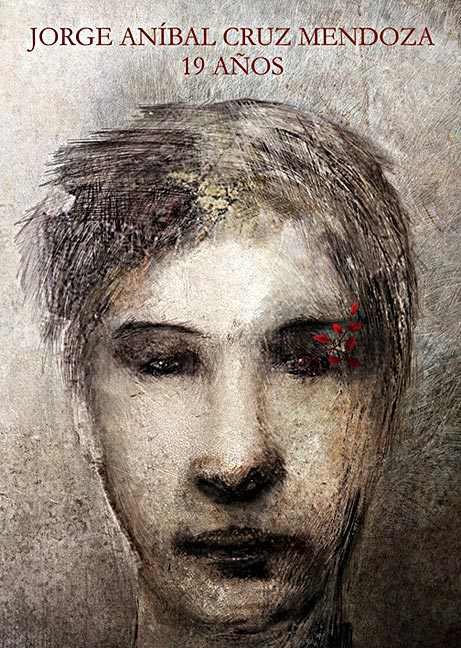

This essay is about the Mexican citizens and artists that are playing a role in that uprising. The posters in this essay came from Mexican artists who created portraits of the 43 missing students disappeared by state “authorities” in Guerrero, Mexico. But before talking about the posters, here is some background on the story.

On Sept. 26, 2014 the police in the town of Iguala, located in the Mexican state of Guerrero, attacked students from the all male “Escuela Normal Raúl Isidro Burgos” teacher’s college in the town of Ayotzinapa. The students were preparing to protest against unfair government hiring practices in education. The officers killed 3 of the Ayotzinapa students in Iguala, wounded 25 others, and also killed 3 bystanders.

The police then rounded up 43 surviving students and handed them over to Guerreros Unidos (United Warriors), one of the criminal drug cartels plaguing the country. It is presumed the drug gang murdered their captives on behalf of the corrupt police.

The next day one of the students, 22-year old Julio César Mondragón, was found dumped on a street in Iguala for all to see. Whether he was a victim of the police or the gang is not known, but a medical examination confirmed that Mondragón had been tortured to death – his face and skull had been completely flayed and both his eyes gouged out. A student at Ayotzinapa for only a month before his death, Mondragón is survived by his 24-year old wife and their 3-month old baby daughter.

After the Iguala story broke, the mayor of Iguala, José Luis Abarca and his wife María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa, went into hiding. They were found in Mexico City and arrested by federal authorities who insist the couple were the “masterminds” behind the attacks on the students.

It is claimed the mayor gave orders to police to apprehend the students before they disrupted a speech to be given by his wife. On Nov. 14, 2014 the government formally charged Abarca for being behind the students’ kidnapping.

Nevertheless, there are far too many open questions regarding the case of the 43 missing students to consider it closed, for instance, where are their bodies?

The Mexican government has unearthed a number of clandestine graves in and around Iguala, but none contain the 43 students. They do however contain remains of dozens of people apparently killed in mass executions. But who were they? Who killed them? Protest signs seen on Mexican streets have some answers – Mexico es una fosa (Mexico is a grave), and Los asesinos están en palacio nacional (the assassins are in the national palace).

At a Nov. 7, 2014 news conference, Mexico’s Attorney General Jesus Murillo Karam claimed that three members of Guerreros Unidos confessed to killing the 43 students, incinerating their bodies and placing their remains in garbage bags, then dumping the contents into a river. Karam said authorities have retrieved one such bag and sent its contents to a medical lab in Austria for DNA analysis. Meanwhile, the families of the missing students asked the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) to investigate the remains found so far. On Nov. 11 the forensic experts reported that the remains did not have “biological kinship” with the missing students.

What the Ayotzinapa tragedy has revealed about Mexico is that large sectors of the state apparatus – police, armed forces, courts, and politicians – have merged with the deadly drug cartels. This merger is aptly described by the signs now carried in the streets by protestors identifying those that kidnapped the 43 students, Fue El Estado – “It was the state.”

The shadow narco terror state incorporates municipal, state, and federal officials, and spends much of its time in the drug business. A 2012 article by CNN stated that Mexican drug cartels annually move $39 billion worth of cocaine and heroin into the United States. What no one will say is that Mexicans are dying like flies to support America’s drug habit.

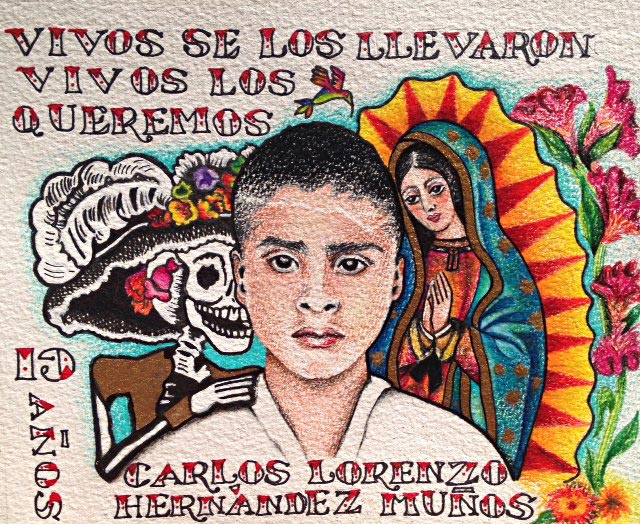

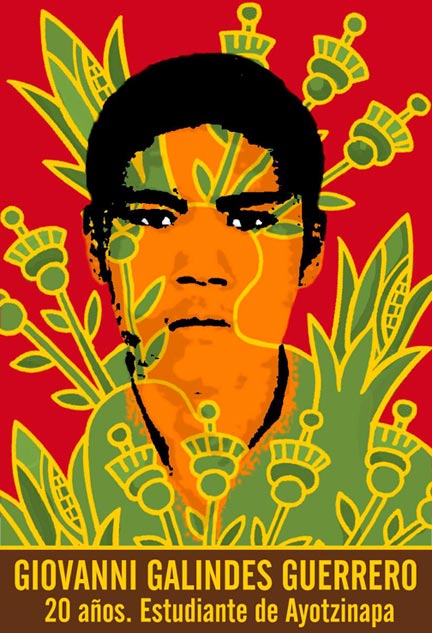

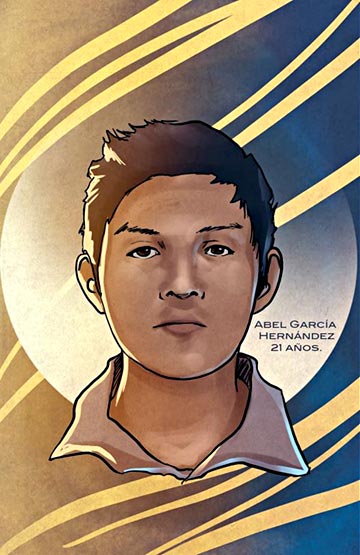

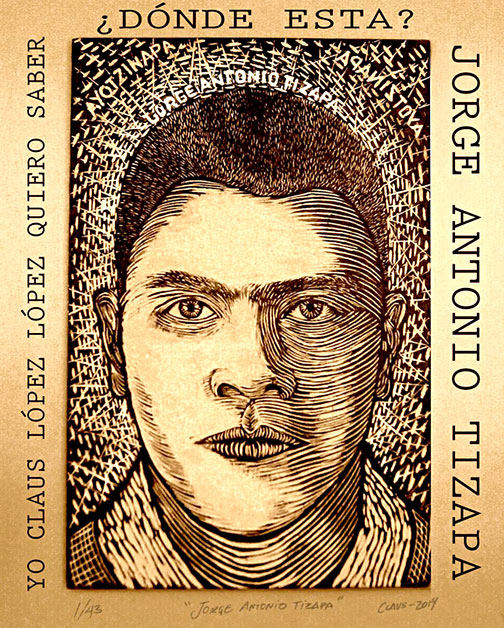

The posters displayed in this article came from #IlustradoresConAyotzinapa, a Mexican Tumblr account where over 200 Mexican artists have created portraits of the missing students. The artists began painting the disappeared students to humanize them, to further ingrain them in the public consciousness, and to embolden the Mexican movement for democracy and human rights. The posters on the Tumblr account have been printed out and carried in demonstrations in Mexico and around the world. Some of the posters are produced by amateurs, the majority however are produced by professional artists.

While digital media plays a large part in the production of the posters, a variety of artistic mediums are employed; drawings done in pencil, chalk, or pen and ink, watercolors, linoleum and woodcut prints, paintings in acrylic or oils. Even sculptural and embroidered works. A number of posters offer serious treatments of the subject matter, others are humorous and fanciful in the Mexican folkloric tradition. All are touching and deeply compassionate.

The artists at the Tumblr account have apparently inspired others; in this video artists in Chilpancingo, the capital of Guerrero, paint portraits of the students in a public square.

The Ayotzinapa posters bring up an important question for artists everywhere. What is the purpose of art? Is it just a commodity for wealthy elites? The Ayotzinapa posters are perfect examples of art springing from the people, the very antithesis of the detached and “apolitical” postmodern art found in today’s museums and galleries. The posters were done for a pure and noble social purpose, they defy the politics of the so-called art world – obsessed as it is with stardom and ostentatious wealth. Those making the Ayotzinapa posters will likely never appear in museums or galleries, but their creations have deeply worked their way into the hearts and minds of the people, expanding and deepening the very definition of Mexican culture.

A caption that appears on each portrait on the Ayotzinapa Tumblr account asks a question regarding the portrayed missing student, “I want to know where” he is. In other words the person depicted is a desaparecido – one who has been made to “disappear.”

Desaparecido is a Spanish word that describes a type of repression I first became familiar with during the October 1968 Summer Olympics held in Mexico’s capital. Ten days before the Olympic games began in Aug. 1968, the county’s student movement assembled in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco to demand democracy and human rights.

President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz ordered the plaza cleared with 8,000 soldiers and dozens of tanks, the result was the army killing upwards of 300 students. The regime destroyed the student movement by making its leaders and supporters disappear – through kidnapping, false imprisonment, and murder by state security forces. No one was ever brought to justice for these crimes.

For those who march in Mexico today, Ni 43, No 68 (Not 43 or 68) is a popular slogan that refers to the slaughter in Tlatelolco. Mexicans have not forgotten that President Ordaz was a member of the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional), the same authoritarian party of today’s President Enrique Peña Nieto. In fact, the 43 kidnapped Ayotzinapa students intended to join the annual October 2 protest held in Mexico City to commemorate the events of Tlatelolco in 1968.

The regimes of El Salvador and Guatemala disappeared thousands of their civilians in the 1980s, more than 50,000 in Guatemala and 8,000 in El Salvador. November 16, 2014 marked the 25th anniversary of the U.S. trained Salvadoran Army’s Atlacatl Battalion going onto the campus of the Universidad Centroamericana in San Salvador, and murdering six Jesuit scholars, their housekeeper and her daughter.

Each were shot in the back of the head. Crimes like these became the subject of much of my art during that period. I imagined that Latin America would someday be free of such tyranny – but in today’s Mexico, there are now some 29,000 desaparecidos.

Addressing the disappearance of the 43 students and the wider issue of government corruption and violence, the students and teachers of Mexico’s National School of Dramatic Arts (ENAT), have been doing public performances – interventions if you will – all around the capital. In this amazing YouTube video of one such performance in the courtyard of the Museo Nacional de Arte in Mexico City, the students tell the tale of those gunned down by Iguala police. This is what “performance art” should be all about.

Reading the U.S. media on the current situation in Mexico, one cannot find a single mention that President Enrique Peña Nieto most likely came to power in the 2012 elections due to massive fraud. In poor neighborhoods, the PRI party distributed a purported $8.2 million in pre-paid gift cards for Soriana grocery stores in exchange for votes of Nieto. There were also charges that Nieto and the PRI purchased positive media coverage from Televisa and other media outlets.

Before the 2012 vote count was tallied and announced, Nieto declared himself to be the new president. As hundreds of thousands of Mexicans marched in the streets to oppose his sham election, President Obama called Nieto to congratulate him on his “victory.”

In 1990 the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa said live on Mexican television, that “Mexico is the perfect dictatorship. The perfect dictatorship is not communism, not the USSR, not Fidel Castro; the perfect dictatorship is Mexico, because it is a camouflaged dictatorship.”

Perhaps Obama never heard of Mr. Llosa or his description of the perfect dictatorship. Interestingly enough, Obama has currently said nothing about the upheaval in Mexico. Secretary of State Kerry has been silent, as have all other members of the Obama administration. The only person to offer a comment was Jennifer Psaki, the spokesperson for the State Department, who on Nov. 13, 2014 simply said “We urge all parties to remain calm through the process.”

Maybe President Obama is made uncomfortable by the fact that his administration provides $15 million in military aid to Mexico, up from the $3 million it received in 2009.

Evidently it is difficult for the President to justify his arming a narco terror state while it murders its own people, so it was thought best just to keep quiet.

The Mérida Initiative signed by President Bush in 2008 and since extended by Obama “indefinitely,” provides $2.1 billion to Mexican security forces fighting the so-called drug war. Since 2006 the U.S. government has spent $3 billion on funding the Mexican government’s “war on drugs,” a joke if there ever was one. The US government is indirectly arming the very drug cartels it says it wants to eradicate.

The 2012 election returned the corrupt PRI to power, the authoritarian party that ran Mexico for 70 years. That reign was broken in 2000 when Vicente Fox of the conservative PAN (Partido Acción Nacional) won the presidency, followed by Felipe Calderón of the PAN, who became president in 2006. Calderón will likely be remembered for Mexico’s bloodiest years since the 1910 revolution. In 2006 he supposedly began a war against the drug cartels then running large swaths of Mexico. By the end of Calderón’s six year term, the cartels were stronger than ever and an estimated 110,000 civilians had perished in the conflict.

Placing the deaths of so may innocent Mexican citizens in context, it should be remembered that during the approximately 17-year long Vietnam war, some 60,000 U.S. soldiers were killed in combat. Nearly twice that number of Mexican citizens died in just six years of Calderón’s drug war. Since President Nieto took power in 2012, another 29,000 citizens have perished in the war. Then came the disappearance of the 43 students of Ayotzinapa; it took Nieto 11 days before he said a word about the kidnapping.

During his Nov. 7 news conference announcing the apparent killing of the 43, Attorney General Karam tried to stop questions from the press by saying, “Ya me canse” (I’ve had enough). His words became a rallying cry. Mexican filmmaker Natalia Beristan perhaps said it best when she appeared in a YouTube video response to Karam’s statement. Beristan said: “Señor Murillo Karam, I too am tired. I’m tired of vanished Mexicans, of the killing of women, of the dead, of the decapitated, of the bodies hanging from bridges, of broken families, of mothers without children, of children without fathers. I am tired of the political class that has kidnapped my country, and of the class that corrupts, that lies, that kills. I too am tired.”

There are other filmmakers that share Ms. Beristan’s opinion. On Nov. 11, 2014, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City held its annual film benefit, this time a tribute to Mexican filmmaker, Alfonso Cuaron (Gravity, Children of Men, Y Tu Mamá También, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban). Cuaron wrote a collective statement with fellow Mexican filmmakers Guillermo del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth), and Alejandro González Iñárritu (Birdman), which was read before the elite audience at MoMA by del Toro. The statement read in part:

“This past September, 43 students were kidnapped by the local police in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. After a period of apathy, the authorities only then were forced to search for them, due to the protestations of citizens across the entire country and the world, and they found the first of many, many mass graves. None of these graves contained the remains of the missing students. The bodies within them were those of other anonymous victims. Last week, the general attorney announced that the 43 students were handed over by the police to members of a drug cartel to be executed and burned in a public dump. But even the identity of those charred remains awaits proper DNA.

The federal government argues that these events are all just local violence — not so. As Human Rights Watch observes, these killings and forced disappearances reflect a much broader pattern of abuse and are largely a consequence of the longstanding failure of the Mexican authorities.

We believe that these crimes are systemic and indicate a much greater evil: the blurred lines between organized crime and the high-ranking officials in the Mexican government. We must demand answers about this and we must do it now. We would like to take this opportunity to ask you all to join us in the pain and indignation felt by the families of the disappeared students and of every civilian in Mexico who is living with this atrocious reality on an every day basis and to at least be aware of this systematic human rights violation taking place so often and so close to you.”

In today’s Mexico there is a modern expression that illustrates the country’s agony; Ayotzinapa; Entre el dolor y la esperanza. In English the phrase translates to “Ayotzinapa; Between pain and hope.” The pain emanating from the place is a distillation of Mexico’s entire blood-spattered history, but it is also an anguish recognized by working people no matter where they live. Likewise, the optimism pouring forth from Ayotzinapa, inspires not just Mexicanos but people all across the globe who dream of a better world.

— // —

UPDATES

Videos that document the November 20, 2014 demonstration:

Students of the Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), created this 4 minute video on the Nov. 20, 2014 march.

The Mexican website Animal Policito made a video of the Nov. 20 march that documents the size of the crowds through the use of drone cameras.

“War Cry” video:

Grito de Guerra is a new song produced by a collective of 30 Mexican recording artists. The video for the composition incorporates images from recent demonstrations along with footage of the song being recorded in the studio. On Nov. 27, 2014, Grito will be released on iTunes and other platforms, with the proceeds going to the parents of the missing students.