Dada at New York’s MoMA

In a June 16th New York Times article titled, Dada at MoMa: The Moment When Artists Took Over the Asylum, critic Michael Kimmelman wrote about the rise of Dada:

“When governments were lying, and soldiers were dying, and society looked like it was going bananas. Not unreasonably the Dadaists figured that art’s only sane option, in its impotence, was to go nuts too.”

Kimmelman’s opening remarks concerning the exhibit Dada at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, detracts from Dadaism’s serious intent. Its adherents were not concerned with a society that “looked” like it was going insane – they furiously railed against a society that was insane. The Dadaist objective was not simply to “go nuts too”, it sought a revolutionary course for liberation and the overthrow of bourgeois society.

At the time, millions were dying in the trenches of World War I, where newly invented machines of war butchered soldiers and civilians alike in astounding numbers. In the face of this ferocious mechanized carnage, the art of polite society suddenly became an enormous joke – and from Zurich to New York, Dada rushed in to fill the vacuum.

In reading Michael Kimmelman’s review of the MoMA exhibit, I got the feeling he understood the deeper meanings Dada had for its era, and also the continued reverberations it has in our own time. He hints at our current state of affairs when he writes, “Politicians were responsible for mass murder, advertisers were conmen, the press self-censoring. So Dadaists figured it was time to throw away the rules.”

But Kimmelman otherwise refrains from making direct comparisons to our present-day morass. Still, he’s a perceptive fellow for writing that MoMA’s exhibit, as “an official survey” is “an oxymoron.”

He astutely stresses that “nearly all 450 or so objects in it look elegant, which they were certainly never intended to look.” Indeed, the Dadaists did not aim to please, and would no doubt be horrified that their works had been enshrined in a mausoleum-like setting, stripped of content and outrage.

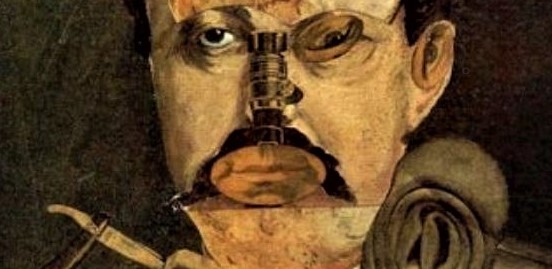

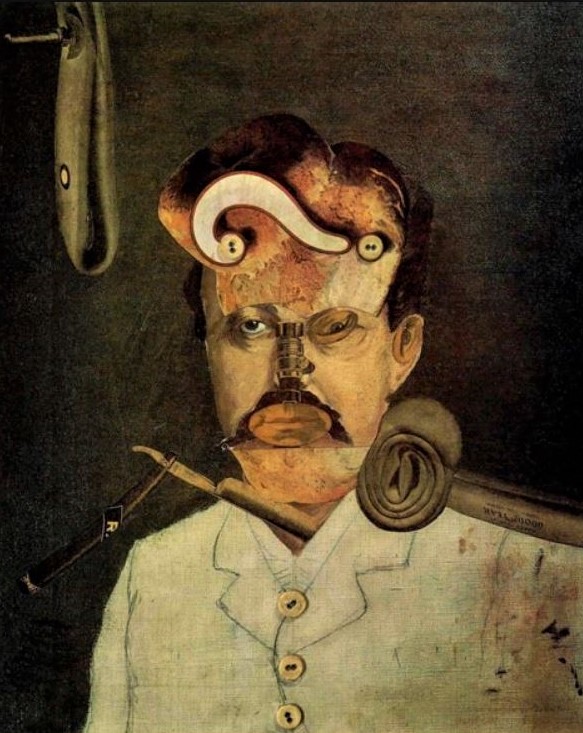

One of the Dadaist mischief makers featured in the MoMA exhibit is George Grosz, and his caustic diatribes aptly sum up the non-conformist stance of Dadaism. In a letter he wrote in 1916, Grosz described his feelings about his fellow Germans:

“It is true I am opposed to war; that is to say I am opposed to any system that coerces me. From an aesthetic point of view, on the other hand, I rejoice over every German who dies a hero’s death on the field of honor (how touching!) To be a German means invariably to be crude, stupid, ugly, fat and inflexible, it means to be unable to climb up a ladder at forty, to be badly dressed, to be a German means: to be a reactionary of the worst kind; it means only one amongst a hundred will, occasionally, wash all over.

One asks oneself how it is possible that there are millions of people completely lacking a soul, unable to observe real events soberly, people whose dull and stupid eyes have been blinkered ever since they were small, whose minds have been crammed with the emblems of stultifying reaction, such as God, fatherland, and militarism.

How is it possible to boast publicly that we are one of the most enlightened nations, when the worse possible principles are already disseminated in schools—principles which, from the very beginning, gag every vestige of freedom of the individual, but instead educate him to become one who follows the crowd, devoid of independent thought, feelings or will.”

Such thoughts were made visibly manifest in Grosz’s artworks and the shocking creations of his compatriots. They attacked conservatism, militarism, ultra-nationalism; it’s not hard to imagine how this was all received at the time by German society as it inexorably edged its way towards fascism. In 1920, Grosz, along with fellow artists Raoul Hausmann, and John Heartfield, organized the First International Dada Fair at the Berlin art gallery of Dr. Otto Burchard.

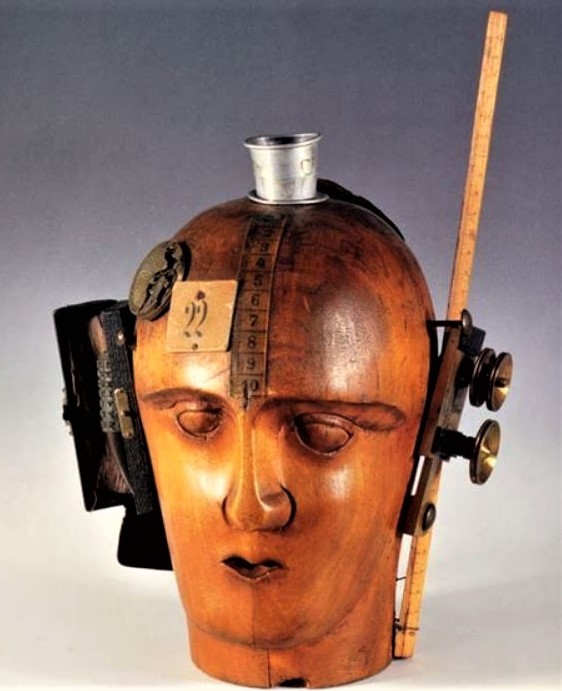

The exhibit displayed 174 paintings, collages and objects by Max Ernst, Otto Dix, Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, George Grosz, Rudolf Schlichter, and others. The exhibit included Grosz’s portfolio of drawings, Gott mit uns (God is with us), which included a sketch of a crucified Jesus wearing a gasmask and combat boots.

From the ceiling of one of the exhibit rooms, Schlichter displayed the effigy of a German soldier with the head of a pig. The exhibit outraged patriotic citizens, and the authorities charged Dr. Buchard, Grosz, Heartfield, and Schlichter of “grossly insulting the German army.” At their trial Grosz and Heartfield were fined, while the other defendants were acquitted.

The German Dadaists were certainly reviled as unpatriotic, anti-German, and dangerous to the war effort, but who today would dare say they were wrong? While the artifacts of the Dada explosion are now safely tucked away in the halls of MoMA, depoliticized and presented as objects of mere aesthetic interest, we should recall the intent of the original movement.

If, as Michael Kimmelman put it, Dada represented a time past when the “artists took over the asylum,” we must asked ourselves…”where are the artists of today who will challenge the weaponized madhouse?”